As their name suggests, by-the-wind sailor jellyfish know how to catch a breeze. Using a stiff, translucent sail propped an inch above the surface of the ocean, these teacup-sized organisms skim along the water dangling a fringe of delicate purple tentacles just below the surface to capture zooplankton and larval fish as they travel.

At the mercy of the wind, these jellies can wash ashore and strand — sometimes numbering in the trillions — on beaches around the world, including up and down the U.S. West Coast. And while these mass stranding events are hard to miss, very little actually is known about how or why they happen.

Now, thanks to 20 years of observations from thousands of citizen scientists, University of Washington researchers have discovered distinct patterns in the mass strandings of by-the-wind sailors, also called Velella velella. Specifically, large strandings happened simultaneously from the northwest tip of Washington south to the Mendocino coast in California, and in years when winters were warmer than usual. The results were published March 18 in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series.

“Citizen scientists have collected the largest and longest dataset on mass strandings of this jelly in the world,” said senior author Julia Parrish, a professor in the UW School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences and executive director of the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team, known as COASST.

“This paper contributes to fundamental scientific knowledge of this organism in a way that traditional ‘mainstream’ marine science has been unable to do. Thousands of trained, dedicated observers are better than any satellite because they know their beach and can alert us if something is weird or unusual.”

COASST’s citizen scientists are trained to search for and identify carcasses of marine birds that have washed ashore at sites from northern California to the Arctic Circle. Participants are asked to record and submit photos of anything strange or different they see on their stretch of beach.

In 2019, program managers received an email from COASSTers in Oregon who had expected to see Velella on their beach based on past observations, but hadn’t. That prompted COASST scientists to comb the database — 23,265 surveys in total — to see if others had taken note of these jellies over the years. This “data-mining” returned 465 reports of Velella littering 293 beaches, often in more than one year.

“On the water, Velella are beautiful, fragile creatures. When they wash ashore, these jellies quickly dry to the consistency of potato chips. During a mass stranding it’s like walking on a crunchy carpet,” Parrish said. “So of course, COASSTers reported in. Suddenly, we realized we had the largest dataset about Velella velella anywhere in the world.”

In analyzing the citizen science observations, UW researchers discovered that most by-the-wind sailors wash ashore on West Coast beaches during the spring, when the winds shift and push the organisms to shore. However, their analysis also revealed truly massive stranding events in 2003-2005 and again in 2015-2019. During the later years, jelly carcasses covered more than 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) of continuous coastline, all within a single two-week window between mid-March to mid-April.

The second period corresponds with the timing of the long-lasting marine heat wave known as “the blob” — also to blame for the largest seabird die-off of common murres, as well as mass die-offs of Cassin’s auklets, sea lions and baleen whales.

The researchers hypothesized that warmer winters during these years allowed for populations of by-the-wind sailors to spike in the open ocean. Then, when the winds shifted in the spring, massive numbers of the jellies were swept to shore and stranded.

Put another way — and though many ultimately end up dying on beaches — the jellies appear to be “winners” during warmer periods, because they can amass more numbers in the ocean. There’s some evidence that warmer-than-average winters are also calmer and less wavy in the open ocean, allowing increasingly large Velella aggregations to persist, Parrish explained.

“This paper and our data really do suggest that in a warming world, we’re going to have more of these organisms — that is, the ecosystem itself is tipping in the direction of these jellies because they win in warmer conditions,” Parrish said. “A changing climate creates new winners and losers in every ecosystem. What’s scary is that we’re actually documenting that change.”

As warmer winters are expected to increase with climate change, these findings could have clear implications for this jelly population, as well as for the fish they eat and the beaches where they strand and die.

The paper’s lead author is Timothy Jones, a UW postdoctoral researcher in aquatic and fishery sciences. Hillary Burgess, now with the NOAA Office of Marine Debris, is a co-author.

This research was funded by Washington Sea Grant and National Science Foundation.

For more information, contact Parrish at jparrish@uw.edu.

Working toward equity and inclusion is a group/community effort, and members across SAFS peer groups have contributed. We have many graduate students and colleagues to thank for proposing a line-up of speakers for the 2021 Bevan Seminar Series on “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences,” which can be viewed through recordings on the SAFS YouTube channel.

Working toward equity and inclusion is a group/community effort, and members across SAFS peer groups have contributed. We have many graduate students and colleagues to thank for proposing a line-up of speakers for the 2021 Bevan Seminar Series on “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences,” which can be viewed through recordings on the SAFS YouTube channel.

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,

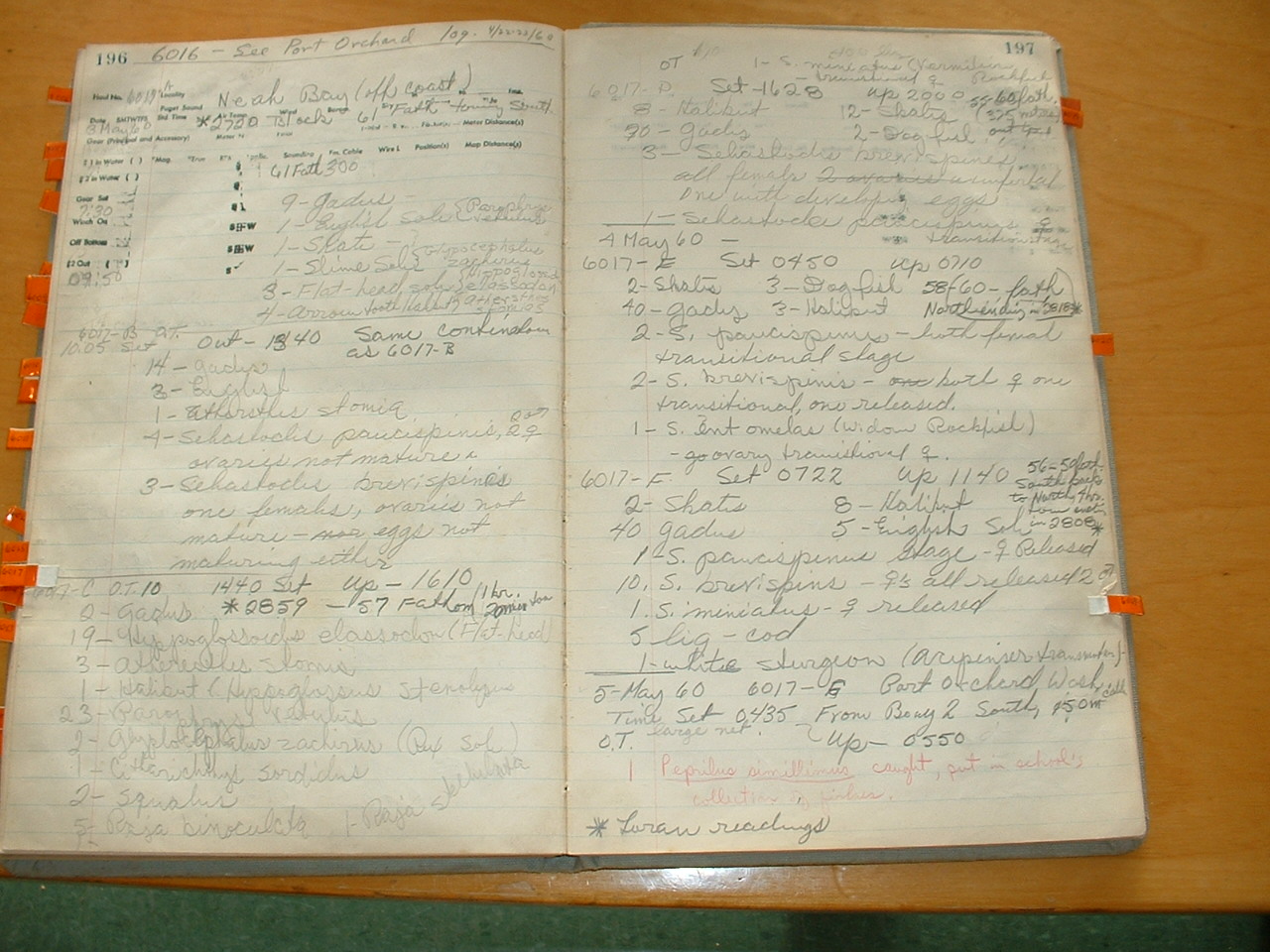

Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Bruce was raised in Iowa City, Iowa, with his three brothers. He studied chemistry and biology at Grinnell College and did his graduate research at UW Fisheries (MS 1965, PhD 1969), where he studied the life history of flathead sole off Orcas Island, Washington.

Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Bruce was raised in Iowa City, Iowa, with his three brothers. He studied chemistry and biology at Grinnell College and did his graduate research at UW Fisheries (MS 1965, PhD 1969), where he studied the life history of flathead sole off Orcas Island, Washington.

Affiliate faculty

Affiliate faculty