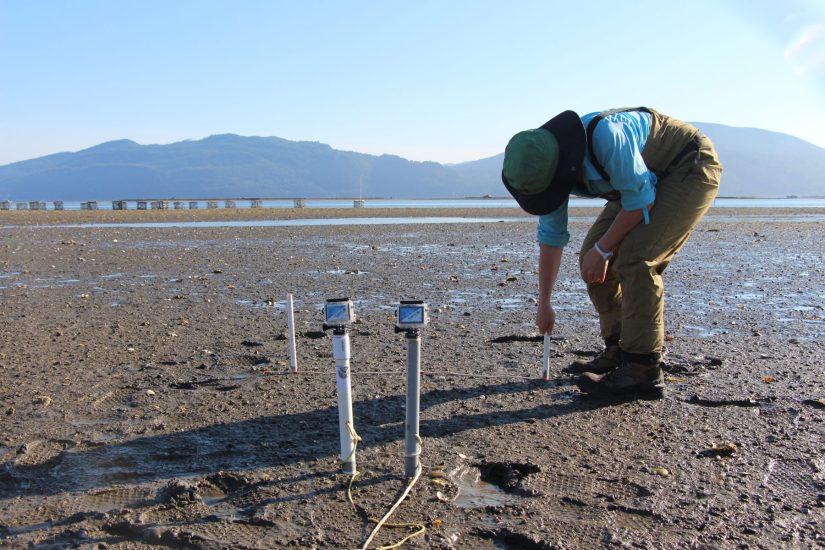

Jason Toft from the UW Wetland Ecosystem Team has been monitoring shoreline armor restoration in Puget Sound for over a decade at sites where artificial armor on beaches has been removed to facilitate the restoration of intertidal areas.

Shoreline armor, also known as seawalls and bulkheads, occurs on over 25% of Puget Sound’s shorelines and was historically installed along homes and infrastructure to address erosion risk. We now know that in many cases armor does not prevent erosion and actually disrupts natural processes that replenish sand and gravel to beaches that provide habitat for fish and wildlife. As more and more sites are being restored, efforts to understand the effectiveness of restoration techniques are critical to developing future best practices and design for armor alternatives.

Partnering with community science groups, Washington Sea Grant, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Vashon Nature Center, Northwest Straits Foundation, Friday Harbor Laboratories, and Sound Data, the collaborative project begun with developing publicly accessible, standardized protocols to allow for widespread shoreline monitoring and training. The team was funded by EPA Puget Sound Geographic Program Funds through the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Department of Natural Resources Habitat Strategic Initiative Lead.

Now existing as the Shoreline Monitoring Database, this tool allows monitoring data to be uploaded and downloaded, and then analyzed. This analysis is the basis for a new publication in Frontiers, with the goal of assessing restoration effectiveness. Restoration projects in Puget Sound usually have the overarching aim of restoring habitat for juvenile salmon and other wildlife.

The paper also brings in other components useful for shoreline managers to be aware of when involved with restoration projects such as the impact of shore type, and wind and wave exposure.

So, what’s the outcome? Often, the sites monitored have proved to have been effectively restored when compared with natural sites that did not have artificial armor installed. There are factors that cause variability in restoration, such as bluffs against a beach or a shallow beach present all the way, and length of time – for example, some sites have only been undergoing restoration for a year, others for many years.

As new funding through the Habitat Strategic Initiative Lead becomes available and the project expands, the collaborative team will add additional years, locations, and types of monitoring at fish and wildlife habitat sites to the existing database. This will ensure improved implementation of future habitat protection and restoration, and address knowledge gaps.

Excitingly, additional funding will also mean a SAFS graduate student will be included in the team starting in Autumn 2024.

Bringing the theme of community science to life, the Vashon Nature Center has been conducting beach surveys on Vashon Island this summer with a group of high school marine science interns and community volunteers. High School internships are supported by a King County Stewardship, Engagement and Learning grant.

- Vashon Nature Center high school marine science interns Molly Newman and Phoenix Moore help with a beach profile on Vashon Island. Photo credit: Maria Metler.

- Vashon Nature Center high school marine science interns Chris Wechkin and Caroline Barnes measure beach wrack cover and width at Piner Point on Vashon Island. Photo credit: Maria Metler.

- Vashon Nature Center marine science interns and Seattle Aquarium Empathy Fellows take a break from restoration monitoring for a belly down dock fouling session. During this lunch break they learn about marine life firsthand from Vashon Nature Center staff. Photo credit: Maria Metler.