Spring Graduation

2022 UW Aquatic Sciences Open House

Ted Pietsch awarded Society for the History of Natural History Founders’ Medal 2022

From from Gina Douglas, President, Society for the History of Natural History

From from Gina Douglas, President, Society for the History of Natural History

SHNH is delighted to award the prestigious SHNH Founder’s Medal this year to Professor Theodore “Ted” W. Pietsch. The Founders’ Medal is awarded to persons who have made a substantial contribution to the study of the history or bibliography of natural history through a sustained record of high-quality publications, and a sustained contribution to dissemination of the history of natural history through practice or curation.

Ted Pietsch is Professor Emeritus in the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, and Curator Emeritus of Fishes at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington. He is a Fellow of the California Academy of Sciences, the Linnean Society of London, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the University of Washington Teaching Academy, and an Honorary Member of the Ichthyological Society of Japan.

He is interested primarily in marine ichthyology, especially the biosystematics, zoogeography, reproductive biology, and behavior of deep-sea fishes. As former curator of the Fish Collection of the University of Washington Burke Museum of Natural History, he is also interested in natural history collections and collection building, and in biotic survey and inventory, the latter best exemplified by a decade-long series of expeditions to collect plants and animals on the islands of the Kuril Archipelago in the Russian Far East.

Ted also led a two-year floral and faunal survey of the Elwha River Valley on the Olympic Peninsula in Western Washington State. A book on the Fishes of the Salish Sea: Puget Sound and the Straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca was published in 2019 by the UW Press.

Ted has also published extensively on the history of science, especially the history of ichthyology. Among the latter are works on the French comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) and his 22-volume Histoire naturelle des poissons (1828–1849); bookdealer, publisher, and secret agent Louis Renard (1678/79–1746) and his Fishes, Crayfishes, and Crabs; the unpublished manuscripts of the seventeenth-century explorer-naturalist Charles Plumier (1646–1704); and on the history of natural history collection-building. His current efforts are directed toward an annotated, illustrated, English translation of Cuvier’s five-volume Histoire des sciences naturelles, depuis leur origine jusqu’a nos jours (1841–1845), the first three volumes of which have already been published.

Definitive works on early ichthyologists include on: Peter Artedi (1705–1735), David Starr Jordan (1851–1931), Charles Henry Gilbert (1859–1928), and Edwin Chapin Starks (1867–1932).

Ted is also a regular contributor to Archives of Natural History published by Edinburgh University Press and his forthcoming article (ANH 49.1 2022 in press) is ‘Charles Plumier’s anatomical drawings and description of the American crocodile, Crocodylus acutus (1694–1697)”.

In speaking of the award, Ted Pietsch said: ‘I am thrilled beyond description!! It’s such a great honour to be recognized in this way’.

More information on the SHNH Founders’ Medal.

Sound solutions for Seattle’s salmon

In 2001, the Nisqually earthquake damaged the integrity of the Elliott Bay seawall along Seattle’s waterfront. Sections of compromised seawall were replaced to form a new ecologically engineered corridor, consisting of intertidal benches to elevate the seafloor, textured seawall to provide refuge and encourage invertebrate colonization, and glass blocks on the above sidewalk to increase ambient light to mitigate habitat degradation and benefit salmon.

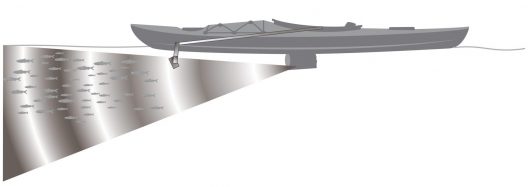

Juvenile salmon utilize shallow shoreline habitat for foraging and refuge from predators. Assessment of salmon populations along these revitalized structures has traditionally relied on visual observation methods, like snorkel surveys. Now, researchers are also turning to novel sonar applications to monitor fish from the surface.

identical location, shown at an uncommonly low tide (right). Kerry Accola

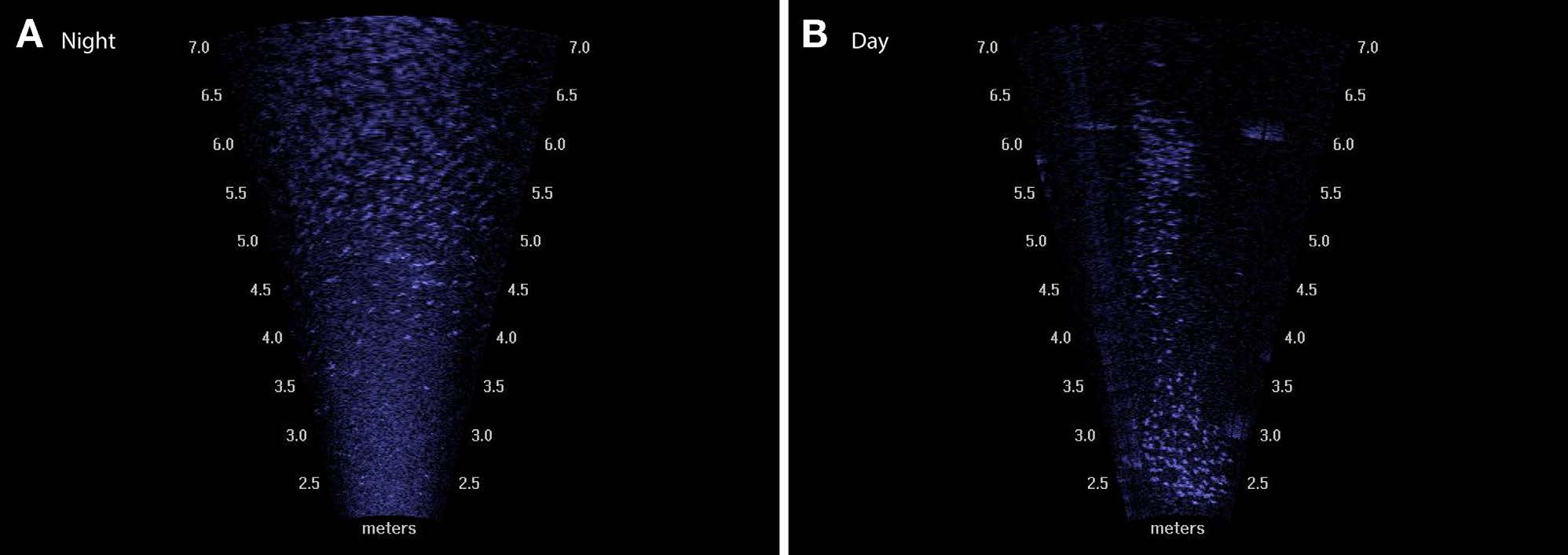

By mounting a specialized mobile sonar called a DIDSON (Dual-frequency IDentification SONar) under a kayak, UW research scientist Kerry Accola is able to count the juvenile salmon along the shoreline from the water’s surface. The sonar is capable of capturing high fidelity images during the day and also the night, when normal visibility is greatly reduced.

These new surveys provided salmon counts twice that of visual surveys and revealed behavioral details previously unknown to researchers. The presence of juvenile salmon at night was found to be twice that of the day, and counts were one-and-a-half times higher at night during times of high salmon concentrations. The study results were published as two companion papers in Marine Ecology Progress Series on January 20 and April 7.

Accola recalls that this new survey idea was a bit of a gamble at first. DIDSONs are generally placed in a static position in rivers and capture horizontal data as fish swim by. It wasn’t known how the additional variables of the moving kayak, shifting backgrounds, size of the fish, and marine debris would influence the sonar’s images. To her delight, the sonar performed better than expected; successfully producing high resolution images of juvenile salmon beneath the kayak.

“The images generated by the sonar are so high fidelity that it is close to looking at them optically,” said Accola. “You can’t see colors or the fins on them, but you really see that they are salmon.”

Her familiarity with the size, shape, and schooling behavior allowed Accola to correctly identify fish from the images. The relatively low biodiversity of fish along the seawall was also advantageous, although as the season went on, it became more challenging as other species began schooling in the study sites.

The researchers discovered that juvenile salmon are using the new eco-engineered corridor with much more frequency than old habitats like piers. Their findings show many salmon along the ends of piers early in the season before they move offshore, indicating they’re going around the pier, rather than beneath it.

“A lot of the salmon are still avoiding the area directly beneath the piers,” said Accola. “We found more salmon along old pier ends at night, meaning they’re migrating around those old ends when they don’t have access to the new corridor.”

Salmon were found in considerably higher numbers at night than during the day. Based on her observations, Accola hypothesizes that salmon are attracted to the artificial light emitted by the city.

Artificial light is known to negatively impact species and ecosystems. In Lake Washington, it was found that juvenile salmon experienced increased predation, as predators used the light to aid in hunting; the light also appeared to delay salmon migration. Ironically, Accola and the team believe the artificial light may be attracting the juvenile salmon to the nearshore at night, which includes the new corridor. Future research will continue to monitor salmon at night to determine if they are also using the light to find food.

This research was conducted throughout 2019 and primarily identified chum and Chinook salmon. The various species of Pacific salmon have a wide range of migration patterns and behaviors, highlighting the need for annual studies. The team is planning to continue to monitor Seattle’s seawall restoration in order to gain insight on how to improve local salmon populations.

Coauthors include John Horne, professor at the University of Washington School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences (UW SAFS), along with Jeffery Cordell and Jason Toft of the Wetland Ecosystem Team also at UW SAFS. This research was funded by Washington Sea Grant, with a matching contribution from the Seattle Department of Transportation.

For more information, contact Kerry Accola.

SAFS Research Roundup: Washington’s Sea Otters and Whale Twins

New model improves accuracy of Washington State’s sea otter estimates

Graduate student Jessie Hale (Laidre Lab) recently published a paper rethinking the status, trends, and equilibrium abundance estimates of Washington State’s sea otter population on January 27 in The Journal of Wildlife Management.

Reintroduced after being locally extirpated from Washington’s coastal waters, sea otters (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) have steadily increased in number over the past 50 years. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) has outlined two goals for recovery: a target population level and a target geographic distribution. Criteria for these thresholds are determined by estimates of population abundance, equilibrium abundance, and geographic distribution. In 2018, WDFW downlisted the sea otter from state endangered to state threatened as the best available information indicated the population had achieved a 3-year average of 1,752 individuals, exceeding 60% of the previously estimated equilibrium abundance threshold for downlisting (1,640 individuals).

The new model developed by Hale and her co-authors improves upon previous analyses of sea otter population dynamics in Washington by partitioning and quantifying sources of estimation error to estimate population dynamics, by providing robust estimates of equilibrium abundance, and by simulating long-term population growth and range expansion under a range of realistic parameters. The authors state that this population model can provide a template for studying the recovery of other small, fragmented populations of endangered or translocated species.

Included in the study results are estimates of equilibrium abundance considerably higher than what earlier models have shown, and under these new estimates, Washington’s sea otter population has not yet reached the 60% threshold required for downlisting.

The authors recommend the WDFW incorporate these new estimates in future decision-making processes for sea otters. Their forward projections of population dynamics also highlight the potential for increased competition between sea otters and valuable state and tribal shellfisheries, as sea otters are, in general, predicted to continue to increase in number and expand their geographic range in Washington.

“This work is the product of a large and long-term collaborative effort to study sea otters in Washington State and highlights the importance of long-term monitoring efforts in understanding sea otter population dynamics,” added Jessie.

Learn more about Jessie’s sea otter research

Prevalence of identical twins and twin survival rates in whales

A new UW study investigated the proportions of identical twins and twin survival rates in whales. Utilizing whaling data from 1908 to 2020, Ruth Drinkwater (BS 2021) and co-author Trevor Branch examined the instances of multiple pregnancies in 16 species of whales. They found that .87% (2,197 out of 252,651) of pregnancies resulted in multiple fetuses, including 12 instances of five or more fetuses. The results were published April 1 in Marine Mammal Science and were the culmination of her capstone project.

The authors then estimated the proportion of identical twins in six of the sixteen species, and found identical twins to be less common than fraternal twins in all six species, excluding humpback whales. Similar to human statistics, the proportion of identical twins is one-third of all twins. Furthermore, strong evidence was found that twin survival declined with fetal length in blue, sei, and fin whales, but not in sperm, humpback, and Antarctic minke whales.

The study shows that successful births of multiples in large whales is exceedingly rare, and thus in predicting future population growth, births can be assumed to be single.

Spring Celebration 2022 honors 2021-22 UW Environment award winners

Julian Olden named fellow of Ecological Society of America

The Scientists Fighting for Parasite Conservation

Protected tropical forest sees major bird declines over 40 years

Deep in a Panamanian rain forest, bird populations have been quietly declining for 44 years. A new University of Illinois-led study shows a whopping 70% of understory bird species declined in the forest between 1977 and 2020. And the vast majority of those are down by half or more.

“Many of these are species you would expect to be doing fine in a 22,000-hectare national park that has experienced no major land use change for at least 50 years,” says Henry Pollock, postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences (NRES) at U of I and lead author on the study. “It was very surprising.”

Concerning is Jeff Brawn’s word for it. Brawn is Levenick Chair in Sustainability in NRES and a co-author on the study. He’s also investigated birds at the study site, Parque Nacional Soberanía, for more than 30 years.

“This is one of the longest, if not the longest, study of its kind in the Neotropics,” Brawn says. “Of course, it’s only one park. We can’t necessarily generalize to the whole region and say the sky is falling, but it’s quite concerning.”

Loss of birds from any habitat can threaten the integrity of the entire ecosystem, Pollock says. In the Neotropics, these birds are key seed dispersers, pollinators, and insect consumers. Fewer birds could threaten tree reproduction and regeneration, impacting the entire structure of the forest, a pattern shown elsewhere after major bird declines.

But the researchers haven’t looked at the impacts or the underlying causes yet. Putting first things first, Pollock, Brawn, and their colleagues focused on documenting the numbers.

SAFS Professor Emeritus Jim Karr began a long-term bird study in Panama 55 years ago while he was a PhD student and later as a professor of ecology at the University of Illinois. He explains that the core of the current study design and its methodology were initiated in 1977. The study continues to this day under its third generation of leadership.

Each year, members of the team set up mist nets in the rainy and dry seasons to capture birds moving through the study site. Mist nets gently entangle birds, allowing researchers to carefully pluck them out. They then identify, measure, and band the birds before releasing them, unharmed, back into the forest.

“Long-term studies like these are essential,” Karr adds, “First, to document patterns in nature and, second, to untangle the causes and consequences of those patterns for conservation and for the long-term health of life on Earth, both human and nonhuman.”

Over 43 years and more than 84,000 sampling hours, the researchers captured more than 15,000 unique birds representing nearly 150 species and gathered sufficient data to track 57 of those. The researchers noted declines in 40 species, or 70%, and 35 species lost at least half of their initial numbers. Only two species – a hummingbird and a puffbird – increased.

“At the beginning of the study in 1977, we’d catch 10 or 15 of many species. And then by 2020, for a lot of species, that would be down to five or six individuals,” Pollock says.

Although the birds represented a wide variety of guilds – groups that specialize on the same food resources – the researchers noted declines across three broader categories: common forest birds; species that migrate seasonally across elevations; and “edge” species that specialize in transition zones between open and closed-canopy forest.

Brawn says the decline among common species is most alarming.

“The bottom line is these are birds that should be doing well in that forest. And for whatever reason, they aren’t. We were very surprised.”

Declines in the other two groups were less remarkable. Birds that migrate to high elevations require some degree of forest connectivity to be successful, but forest in Panama – like most places – became increasingly fragmented in the last several decades.

Edge species were hardest hit, most declining by 90% or more. But Pollock and Brawn weren’t surprised. In fact, the disappearance of edge species boosted their confidence in their results. That’s because, 40 years ago, a paved access road cut through the site. It created the ideal edge habitat for birds that like openings in the forest canopy. But over time, the road stopped being maintained and has since turned into a small gravel road and the forest canopy filled in overhead.

“The fact that edge species went away when the road did is not concerning,” Pollock says. “It shows what we would expect with forest maturation and the loss of those successional habitats.”

The researchers are reluctant to generalize their results beyond their study site, pointing out the scarcity of similar sampling efforts throughout the tropics.

“Right now, this is really the only window we have into what’s going on in tropical bird populations,” Pollock says. “Our results beg the question of whether this is happening across the region, but unfortunately we can’t answer that. Instead, our study highlights the lack of data in the tropics and how important these long-term studies are.”

The study wasn’t designed to explain why birds are declining in the forest, but the researchers have some ideas they want to follow up on. Things like changing amounts of rainfall, food resources, and reproductive rates, many of which may be tied to climate change.

But whatever the cause, the researchers expressed urgency to figure it out.

“Almost half the world’s birds are in the Neotropics, but we really don’t have a good handle on the trajectories of their populations. So, I think it’s very important more ecological studies be done where we can establish trends and mechanisms of decline in these populations,” Brawn says. “And we need to do it damn quick.”

The article, “Long-term monitoring reveals widespread and severe declines of understory birds in a protected Neotropical forest,” is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Authors include Henry Pollock, Judith Toms, Corey Tarwater, Thomas Benson, James Karr, and Jeffrey Brawn.

Funding for the work was provided by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), the National Science Foundation, the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences (ACES), the U. S. Department of Defense, Earthwatch, the National Geographic Society, the American Philosophical Society, the Biodiversity Institute at the University of Wyoming, and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

The Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences is in the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

This release was adapted from text provided by Lauren Quinn at the University of Illinois.