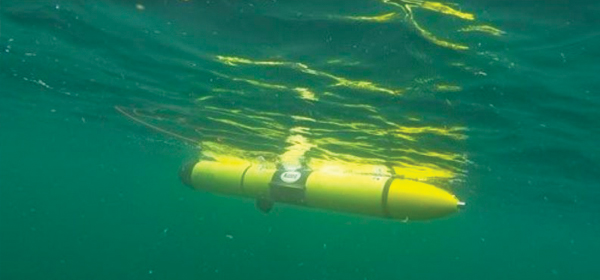

Glider in the Gulf

In July, Professor John Horne eagerly returned to the field after more than a year of pandemic-related delays. As part of a multi-institutional science team, John set sail aboard the R/V Point Sur from Gulfport, Mississippi, testing new technologies to study deeper waters of the Gulf of Mexico in more detail. This voyage was also the first opportunity for John and his team to deploy the new glider technology they have been developing.

The glider John’s team deployed was programmed to descend and ascend in the water column where an onboard echosounder was used to measure densities and sizes of macroscopic animals. Advances in glider technology have allowed for the availability of this data in what John calls “glider time” (as opposed to real-time), represented by when the glider surfaces and connects with a satellite to transmit the observed data. Previously, the volume and cost to transmit data over satellite have limited what data gliders can transmit from field measurements.

“The challenge was how do you compress the data or do something else.”

This problem inspired John and his team to develop the glider’s first “acoustic brain,” an additional small computer integrated into the sensor package.

“I took a suite of metrics that I developed for monitoring the distribution and density of water-column biology at an ocean observatory and for marine renewable energy sites and thought it could be used to solve the data crunch problem,” John said. “The small onboard computer processes the raw acoustic data to produce a suite of descriptors that characterize the distribution of biomass in the water column and transmits these descriptors to the pilots and scientists who deployed the glider.”

An additional step developed by colleagues at the University of South Florida indexes backscatter data using color, which is then used to create a low-resolution echogram. Glider operators are now able to see two things: an echogram picture that you wouldn’t get from the indices alone, plus a set of metrics, called Echometics, transmitted through the satellite in glider time.

John explains that the volume of the Echometric values and the coarse echogram are about 40 times less than the raw data alone and provides the team with even more information as they now have a more complete view of what the gilder sees while deployed. Operators can now alter the sampling path of the glider in response to something they see or because they want to investigate an area in more detail.

John believes the value of this new glider technology will become even more apparent by pairing it with other emerging technologies. A parallel experiment aboard the R/V Point Sur, executed by the National Geographic Exploration Technology Lab, tested a network of underwater driftcams. These stereo and video cameras are encased in waterproof housings and can be controlled through an underwater acoustic modem to visually monitor different depths. Acoustic information collected by the glider, as well as instruments aboard the R/V Point Sur and an at depth CTD, can all be relayed to the driftcams.

“The idea is that we take the acoustic data from the glider to get the distribution and density of a patch of animals, and then use the driftcams to identify the constituents,” said John. “We could see where the layers are from the acoustics, and then we could direct the driftcams where to go to take the images.”

Overall, the teams were able to successfully integrate these technologies in the field for the first time, and they are excited about the preliminary results. The ambitious next step for John and his collaborators is “autonomous adaptive sampling” or having the glider make its own decisions in real-time while on deployment.

“Imagine surveying an area and you see a very large patch that you want to investigate,” said John. “The glider’s ‘acoustic brain’ can make a decision whether or not to investigate that patch, identify patches if they exceed a certain threshold, or use logic steps to alter its mission to go sample a patch and determine its boundaries. When finished, the glider goes on its way and resumes its original path.”

Learn more about the interdisciplinary team aboard the R/V Point Sur and its various research goals.

John plans to travel to Alaska in September to conduct the initial gear testing of a second glider. Its first mission will be to look at prey fields and distribution of salmon in the Gulf of Alaska in conjunction with the International Year of the Salmon cruise, which is scheduled for February of 2022.