Jim and Lisa Seeb – Off in New Directions

Lisa and Jim Seeb, research professors at SAFS for 13 years, retired at the end of September. Their links to the School, however, stretch far back—both were graduate students in the (then) School of Fisheries (Lisa, PhD 1986 [Gunderson]; Jim PhD 1987) before establishing the first fisheries genetics laboratory in Alaska. After 16 years with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (AD-F&G), they were lured to SAFS in 2007 and have been here ever since. Lisa and Jim have made major contributions to population genetic methods and their application to Pacific salmonids. Their work has improved the conservation and use of these iconic species.

What brought you to fisheries science and SAFS?

Jim: I left the US Air Force in 1974 with a BS in chemistry, four years of GI Bill, and no expectation that my degree would lead to a career. My time in the College of Fisheries (COF) involved informally taking a few classes and diving for specimens to add to Dr. Welander’s collection. I met a very gracious Bill Hershberger, a fairly new assistant professor with little activity in his genetics lab at the time. (Genetics was a boutique field in the COF then.) Hersh gave me a key to his lab and unfettered access to dabble with his equipment and chemicals (for that I remain in awe and will always be grateful). In the 1970s, there was little COF funding available for graduate study, especially in genetics, but I took a class offered by Affiliate Professor Fred Utter, who had access to outside agency funds to promote genetic studies. Fred sponsored me as an MS student and remains a mentor to this day.

Lisa: Becoming a UW graduate student was the result of a circuitous and unlikely journey. After graduation from UC Berkeley, I was urged to pursue graduate school in zoology. I headed to the University of Montana for an MS, quickly becoming interested in population genetics using a frog species as a model. I worked with Fred Allendorf, a UW graduate, who introduced me to Fred Utter and correctly pointed out that there were many more jobs for fish than frog geneticists. After working for a year as Jim’s technician, I applied to the UW and was accepted as a NMFS-funded PhD student to study rockfish with Don Gunderson. Throughout graduate school, I was fortunate to have supportive mentors to help navigate this unlikely journey and provide a welcoming environment for, what was then, an almost exclusively male-dominated profession.

Why the change from ADF&G to SAFS?

Lisa and I arrived at the ADF&G in 1990 with no startup and a small budget. Alaskans recognized the potential of genetics to add to their toolkit for conservation biology, which is rooted in the State constitution. We built a robust program with 20 full-time scientists and technicians who used genomic technologies to monitor and conserve populations of exploited salmonids. Data sampled by the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC) parties provided a base to both develop migration models and to discriminate the origins of fish intercepted in fisheries prosecuted on the high seas.

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF) scouted our program in 2006, suggesting a grant to extend our novel genetics approaches to Asian nations that were a focus of their salmon conservation efforts. While interesting, the GBMF idea was not feasible for us in an agency setting. Ray Hilborn envisioned incorporating our genetics program into the Alaska Salmon Program (ASP) and introduced us to SAFS and Dean Nowell of the College of Ocean and Fishery Science. We were thrilled to leave the confines of a strict agency mission, work within the globally renowned ASP, and mentor graduate students and post-docs who would provide a legacy that we would otherwise not achieve.

What were some of the most rewarding aspects of your time at SAFS?

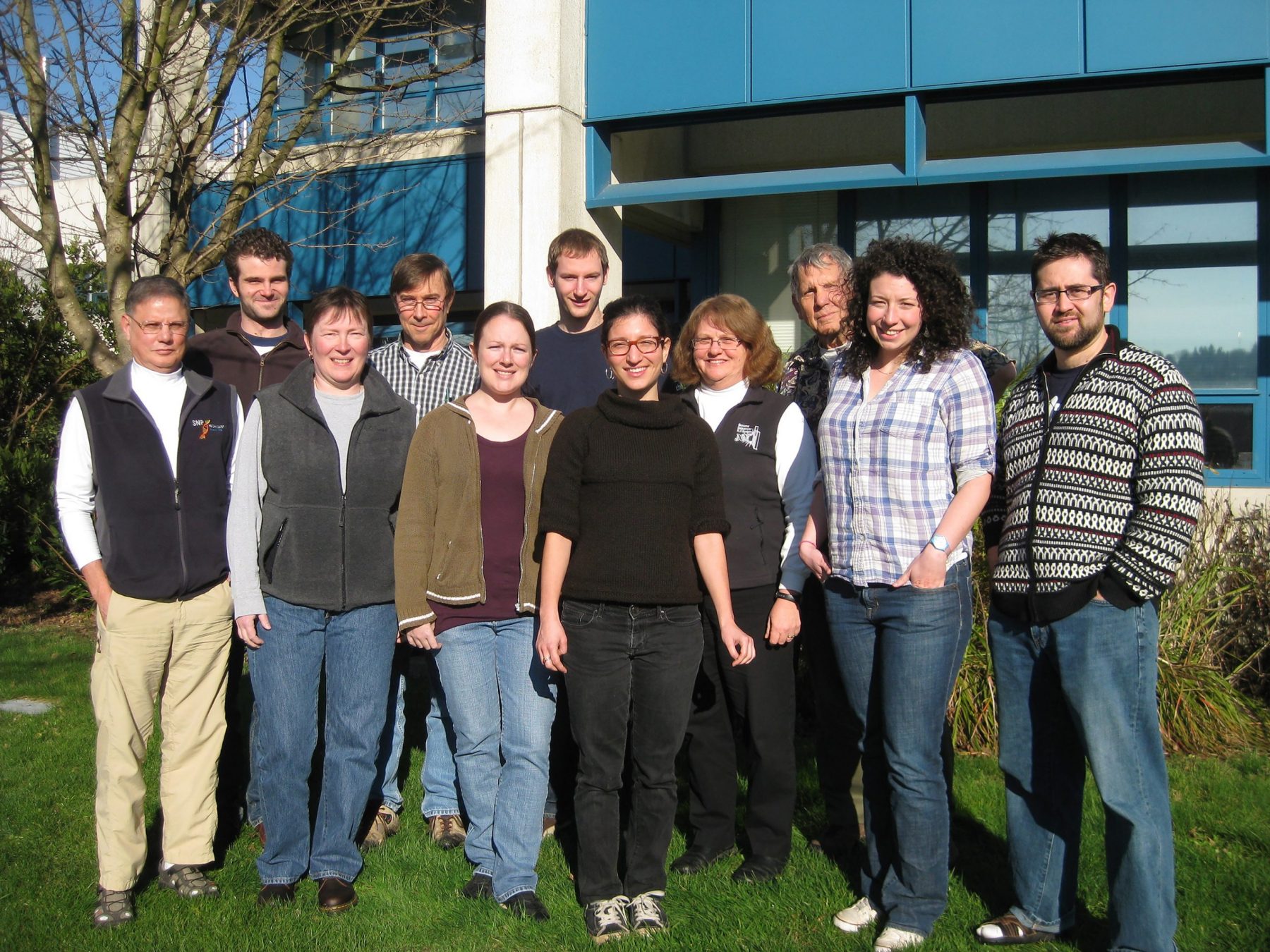

Working with the very talented students, post-docs, and faculty. Our seed funding enabled us to host workshops, attract amazing students, and explore the complexities of genome duplication in salmonids—things that we could not do before. Our lab members paved the way into high-throughput DNA sequencing and applied bioinformatics for fisheries that serve as a model for many conservation genetics labs today.

What is your impression of the legacy of SAFS in terms of population genetics in aquatic systems?

One only needs to look at the mentoring tree to trace the influence of SAFS in population genetics of salmonids. Branches lead through NWFSC and SAFS researchers, beginning with Fred Utter, Bill Hershberger, and Paul Bentzen, and continuing through Kerry Naish, Lorenz Hauser, Steven Roberts, and our lab. Today, many students worldwide can trace the link to SAFS through their mentors or earlier generations of mentors.

- Jim Seeb at Kobuk River in 1991

- Lisa at Kobuk River Alaska in 1991

Describe some projects that had the largest impact.

A peripheral project that had a transformational impact 30 years ago was one of the first wildlife applications of forensic genetics. In January 1989, ADF&G contacted us after they confiscated a boatload of red king crab allegedly taken during a time/area closure. Our analysis of the confiscated samples showed that they could not have originated from near Adak Island, the only area open to fishing. Based on these data, the skipper agreed to pay the state $565,000—still the largest fine for fishing violations in Alaska. It is difficult to identify individual projects, but two themes stand out. During the 1990s and early 2000s, there was some stagnation in the use of genetic technology by natural resource management agencies. In 2001, we sought to incorporate more modern techniques developed in the two human genome projects to provide population genetic information more efficiently and accurately, and by 2005, a series of papers began emerging from our lab that detailed the ”new” SNP technologies for salmonids. The second theme of projects emerged directly from our GBMF opportunity at SAFS. Students and post-docs in our lab, working on commercially important salmonids, constructed a series of high-density genome maps in an effort to identify adaptively important genes; these genome maps are being used to clarify the complexity of chromosome structure and of the duplicated salmonid genomes. Special recognition goes to Carita Pascal who followed us on our technological and geographic journey from Alaska to Seattle and helped many students and post-docs throughout the salmonid community overcome innumerable lab and bioinformatic challenges.

What’s next?

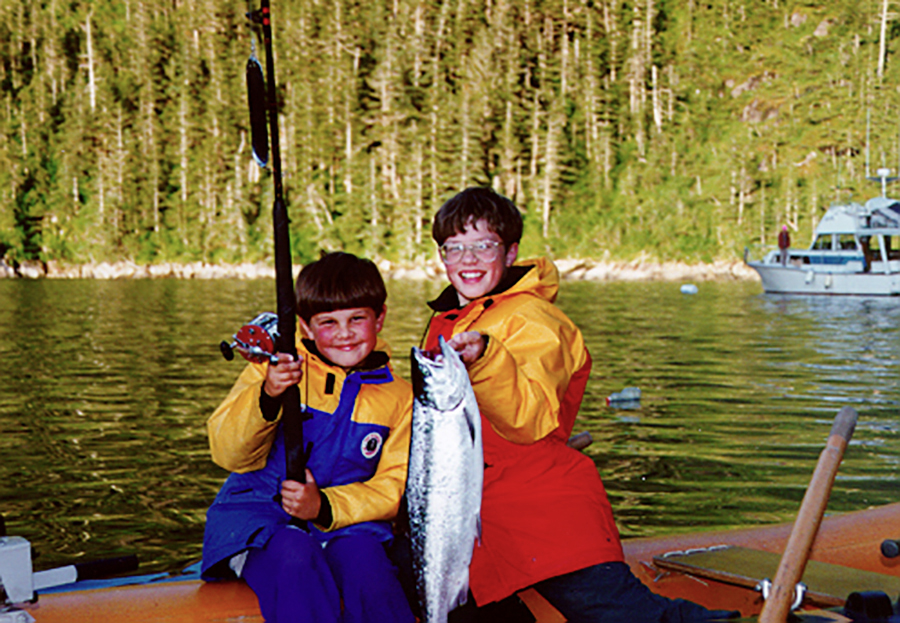

During our first retirement year, we planned to complete projects and collaborate on a few new ones, visit colleagues in Alaska and Chile, cruise with our boat, and become better photographers and fishers. Obviously, life has changed and travel postponed. We continue working on local and international scientific panels and existing and new collaborations. We remain optimistic that we can take our boat to northern British Columbia and Alaska in the future. As always, we look forward to following rapidly emerging advancements in salmonid genomics.