Beyond despair: How can ecosystem restoration enhance human wellbeing?

Ecosystem restoration has historically had a very ecological focus with goals of improving different ecological metrics such as percentage of vegetation cover, presence of fish and other species, ecological functioning, and more. However, while teaching a special interdisciplinary class during her time as a postdoc and co-PI at Duke University, SAFS Assistant Professor, Carter Smith, took a slightly different view: how can ecosystem restoration be used to directly improve human wellbeing?

Recently published in January 2025 in PNAS, this concept is outlined in a new paper that explores how ecosystem restoration can make individuals and communities more resilient through enhancing optimism, making people more connected to their environment, and making people more socially connected. “The original goal of the project was to understand interdisciplinary resilience concepts and how they apply to ecosystem restoration,” Carter said. “As part of our deep dive into the literature, we realized that a lot of people were talking about resilience in restoration focused on ecological or disaster resilience, but there was a real knowledge gap in understanding how restoration can impact social and psychological wellbeing of people.”

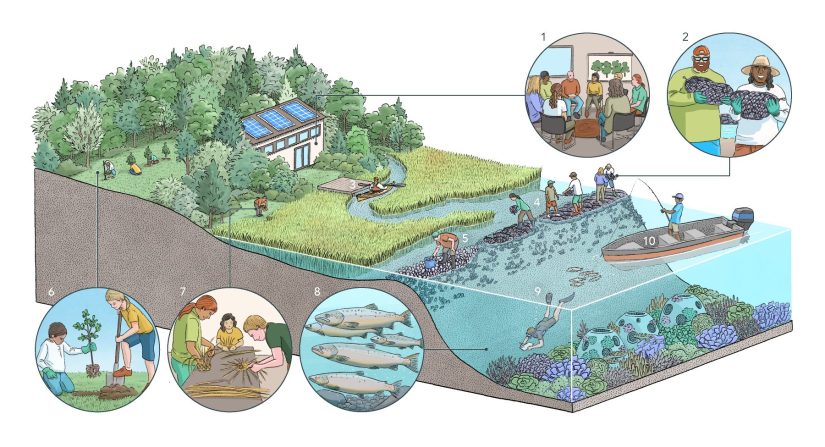

The study sets out these three individual and community-level strengths that the team of researchers thought could be enhanced through restoration. Bringing together scientists, faculty and students from Duke University, University of Adelaide, North Carolina State University and NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science – as part of Duke’s Bass Connections program – the team compiled information about promising community-engaged restoration projects from around the world, and some recommendations for how restoration can be conducted to improve psychosocial resilience through this lens. “Examples of community-based restoration exist on a vast scale, from engaging diverse stakeholders at the initial goal-setting stage of a project to build trust, all the way to biocultural restoration projects that include community workdays and shared meals as a way to build relationships and learn about traditional cultures”, Carter shared.

So what are some of the actionable ways to enhance psychosocial resilience through ecosystem restoration? The answer could be to just bring people into the process wherever and however possible and moving restoration projects from largely technical endeavors to ones which account for human-nature relationships. “Directly engaging community members in the restoration process to assist with planning or implementation, or indirectly by facilitating access to natural areas and creating a place where people can do the activities in nature that they value are some of the ways to do this,” Carter shared. Embedding community spaces around or within restoration projects, such as boardwalks, beach parks, or community centers, are some examples of this.

But caution was advised about further eroding human relationships with the natural world through the technologization of restoration. “There is a huge emphasis in restoration right now on upscaling and technologizing the restoration process – and this will likely be very important for meeting some restoration goals – but we shouldn’t lose sight of the value of community-engaged projects,” Carter said.

Many of us have experienced the benefits of being outside in nature, and it’s a well-studied area in relation to psychological and physical benefits, from reducing anxiety and cardiovascular disease, to helping your nightly slumber. And this is a great place for many people to start. “Getting involved in restoration can be really small and as simple as joining beach cleanups and planting native plants in your backyard,” Carter said.

In a time of general climate pessimism, celebrating success stories is a way to combat climate despair. “A healthy amount of doom and gloom is needed right now to acknowledge the magnitude of the problem we’re facing, but I would encourage people to see hope in the successful restoration stories we’re seeing from across the globe,” Carter added. “I draw a lot of hope and inspiration from learning about biocultural restoration projects that incorporate traditional ecological knowledge, from large-scale seagrass restoration in the Chesapeake Bay, oyster restoration in parts of Australia where oysters were functionally extinct, and from numerous reforestation projects globally.”