Examining the impact of settler colonialism on Indigenous food systems

Working at the intersection of environmental justice, food sovereignty, and community-based research, Nicole Doran is centering Indigenous perspectives in her work. Nicole’s research for her masters degree, as a member of Mark Scheuerell’s Applied Ecology Lab at SAFS, has involved a deep dive into available literature to examine the impact of settler colonialism on Indigenous food systems.

With this year marking the 50th anniversary of the Boldt Decision, which upheld the rights of members of several Western Washington Indigenous tribes to fish in accordance with terms of treaties signed in the 1850s, discussions around this topic remain deeply relevant.

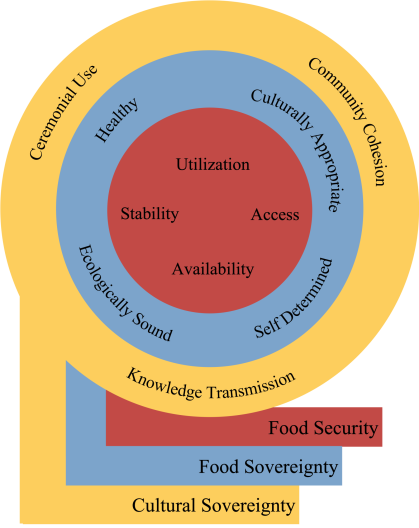

Nicole’s literature review, comprising her first thesis chapter, delved into historical documents, accounts, academic papers, traditional ecological knowledge, and reports. “I’m presenting a framework for understanding the layers of environmental injustice that permeates cultural food systems such as those maintained by Indigenous communities,” she said.

In order to take a deeper look into how Indigenous thoughts about topics such as food sovereignty and access differ from western science, Nicole highlights an example: “When thinking about contaminants and banning fishing, state or federal regulators may decide that any containment above a certain level means fishing should be banned. Indigenous ways of thinking have a different focus on this issue, where either no level of containment is acceptable, or that a particular fish is so important spiritually and traditionally in the community, that it should still be harvested,” she shared.

Digging into the concepts of food sovereignty and food security, and the big impact of environmental justice on Indigenous food systems, Nicole found that there is a key distinction to be made. “A lot of Indigenous communities lack food security, but for ones who have this, it isn’t enough. Food sovereignty is highly important too,” Nicole said. “Is the food they have access to healthy, traditional, and prepared in a self-governed way? Food sovereignty elements are extremely important, but in the eyes of the government for example, who provide food and other commodities – spam, white flour, sugar, oil – this food security is enough.” The topic of limitations on access to traditional and cultural food also brings to the fore issues around the nutritional value and healthiness of commodities provided, which have led to increases in diabetes and heart disease in these communities. In the food literature that Nicole looked into as part of her second chapter on this topic, she found that food security and food sovereignty weren’t considered together, but they should be.

Bringing all of this work together in her third chapter, Nicole explored how to build resilience from an ecology perspective. Indigenous communities recognize that our world is always in flux – climate, food, environment, resources – and it’s an important aspect to consider when thinking about food systems. “The principle of being in a relationship with environments in traditional ways, not separated from nature, but rather tightly interwoven through reciprocal relationships, is incredibly important,” Nicole shared, but this has been significantly affected by settler colonialism.

One of the key takeaways Nicole wants to highlight from her research has been the ways in which people should connect with Indigenous ways of thinking and scholarship: “There are a lot of well-meaning people wanting to connect with Indigenous scholars, but the first step is to engage with the land you work on and look more deeply into how science itself has been impacted by settler colonialism”. Another vital learning that Nicole wants to share is the importance of ethical collaboration. “Bringing back the research to the community, sharing the outcomes, speaking openly, and respecting the relationship of trust that has been developed, is so important, and a lesson worth learning for a lot of people working in this space,” she noted.