Taking a deeper look: using fish eye lenses to explore invasive fish impacts on native fish communities

Fighting for the little guy. That’s one of the things Jess Diallo, PhD candidate at SAFS, likes about her work. Her research encapsulates this idea as she explores the impact of invasive fish on native fish food webs, based in a tributary to the lower Colorado River.

Part of Julian Olden’s Freshwater Ecology and Conservation Lab, Jess’ fieldwork in 2021 involved collecting samples for stable isotope analysis, including fish eye lenses, to provide a deeper look into how fish move throughout the food web.

“The two main characters in this story are roundtail chub, a native fish, and green sunfish, an invasive species,” Jess shared. “It’s important to study the impact of invasive species on native populations as the whole ecosystem can be impacted by the predation and competition threat that they pose,” she added.

The invasive fish living in her study site, the Burro Creek basin of the Bill Williams River, a tributary of the lower Colorado River, consist of species introduced throughout the last century, which are now the focus of sport fishing, including bullhead and green sunfish. Native species in this system include roundtail chub, desert sucker and Sonora sucker.

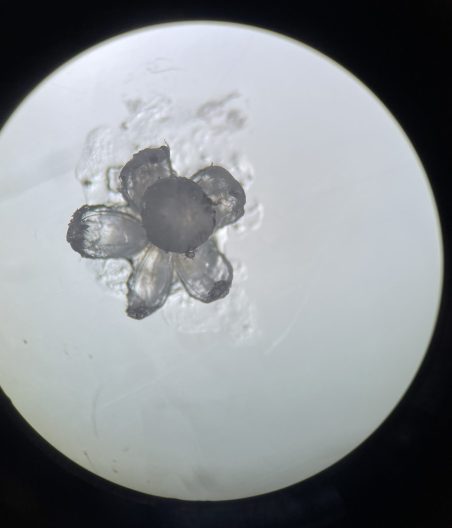

“Using fish eye lenses to conduct stable isotope analysis is a really cool method,” Jess said. “The eye lens grows in concentric spherical layers, building on itself over time. And when you dissect this tissue, you can look through time into how the fish moved through the food web.”

This method allows Jess to see clear shifts in diet throughout an individual’s life, for example from a juvenile fish eating insects, to growing larger and graduating up to eating other fish. Food consumption provides a clear signature in stable isotope analysis, and Jess is interested in exploring how invasive and native fish interact in the food web throughout their lifetime, and the comparison with native fish-only communities.

Studying five species of fish in total, Jess has seen some clear results from the stable isotope data she has collected. “The lifetime trophic trajectories of native fish species are, on average, displaced within the food web when they’re in streams containing invasive species, compared to native-only communities,” Jess shared.

This displacement is seen in lower values of Carbon-13 and Nitrogen-15, meaning a dietary shift from terrestrial to aquatic plant carbon sources and a lower position on the food chain.

Sharing why some streams are inhabited by native-only fish and others have the presence of invasive species, Jess noted that it’s down to the hydrology and climate of the area: “Burro Creek has intermittent streams that flow when there’s rainfall, but become isolated pools during the dry season. This fragmented system means that when invasive fish were introduced in a reservoir on the lower Bill Williams River, their progress upstream was slowed by dry stream sections.”

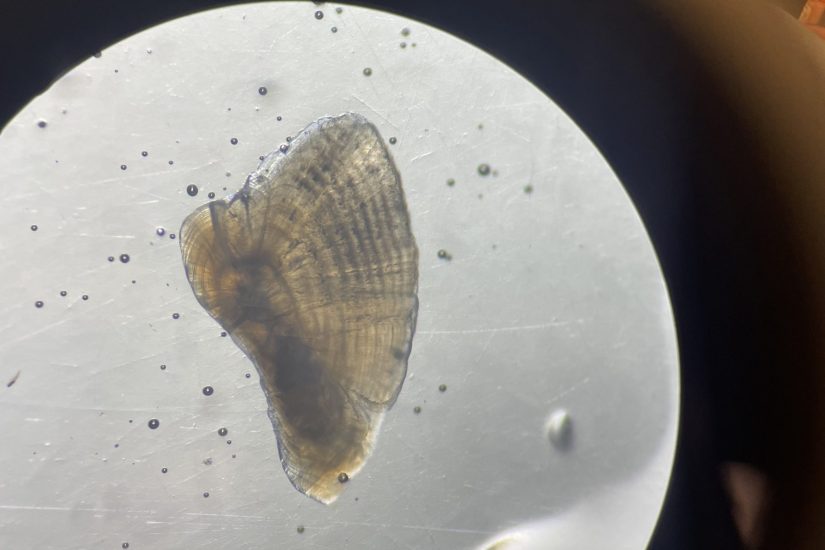

Another area of Jess’ work is using otoliths, the ear stones of fish which can be used to age them, to link the chronological record of stable isotope values to time. “These two parts of a fish, their eye lenses and their otoliths, are two records of a fish’s lifetime. This is really novel research, linking the otoliths to eye lenses, especially for community ecology, so it’s really exciting work to be involved in,” she said.

Jess wants to be able to take all of the individual fish and different species present in the river and put them all on the same timescale. “This is where both methods come in. The fragile, crystalline structure of fish eye lenses mean you can only measure the size of each layer as it’s peeled back, a bit like an onion. These measurements are proportional to fish body size,” she shared. “By using otolith data too, we hope to be able to go from fish body size to fish age and shed insight into the impact of things like season and hydrology on the food web”.

“This work has really highlighted for me the beauty in the tiny things – fish eye lenses, otoliths – and the wealth of information they hold,” Jess said about her research. It has also been an important learning experience when conducting science. Not only did Jess conduct her research in an area facing a myriad of different factors such as water extraction and different land use issues between private and government entities, adding in fish conservation presented a new optic.

“My research was also a steep learning curve and I hope to be able to share new methods and best practices in the future,” Jess said. “This type of research combining stable isotope data from fish eye lenses with otoliths hasn’t been done before, and trying to figure out the best way to peel an eye lens or polish a lapillar otolith taught me an awful lot about these species.” Dissecting at least 400 fish and working on between 1-15 tissue samples from each one, Jess hopes to contribute her learnings through a methods paper to other researchers in the fish ecology field.