Salmon, scales, and spectrometry: analyzing historical fish scales to explore food web changes over time

For over 60 years, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game have collected scales from sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay. Now, these scales are receiving special treatment in a new project led by SAFS graduate student Grace Henry, who is conducting stable isotope analysis to examine how food webs in the North Pacific Ocean have changed since the 1960s.

Chemistry has always been Grace’s biggest interest: “I love chemistry, and for me, it’s the cornerstone of ecological science.” Working with stable isotopes in her pre-graduate studies, Grace wanted to use this method during her thesis work on food webs using historical archived samples.

Utilizing this novel method of Compound Specific Isotope Analysis (CSIA) with historical samples of salmon scales, Grace is exploring if salmon have changed their eating habits, and how ocean composition has changed over time.

“We know that were was a climate regime shift in the 1970s affecting Bristol Bay called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. It’s similar to El Nino in that it’s a long-time period change in regional climate, and for some reason, this shift meant a lot more salmon were coming back to Bristol Bay,” Grace shared.

Grace hypothesizes that maybe part of this increase in salmon was because climate change altered the ocean composition in a positive way for the species. Salmon scales grow much like tree rings. They grow constantly through the salmon’s life and what the salmon is eating is locked into the stable isotopes of the scale. Examining these scales is a way to dig deeper into this hypothesis and see that shift reflected in the isotope analysis. “It’s also possible that this won’t be shown, and that will be interesting in itself as this suggests it will be something else that’s the cause,” she added.

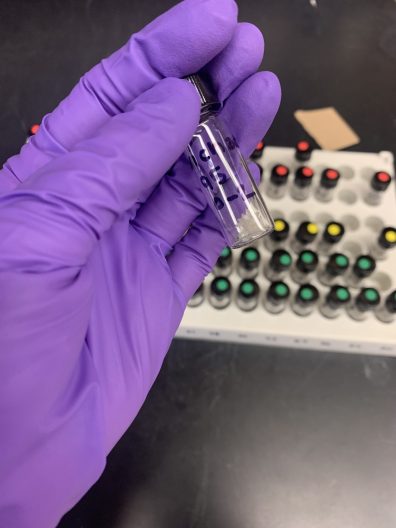

Where do the scales come from? Collected during every season of the sockeye return to Bristol Bay since 1960s, people employed to work in counting towers at the mouth of every river would collect scale samples after conducting fish counts. “These scales are really cool because they save really easily and don’t degrade,” Grace said. “You don’t have to preserve them in a special mixture of chemicals, and so there aren’t any interactions with chemicals when doing the isotope analysis.”

Explaining more about the method she uses for her research; Grace uses a gas chromatograph and mass spectrometer to run all her samples. Her process involves dissolving the scales in hydrochloric acid and then adding a few other chemicals to break apart the proteins into individual amino acids that she can analyze.

“This method is pretty new and not a lot of people use it. It’s exciting to be able to use this method and framework in my research to deliver new insights into the changing diet of sockeye salmon and the ocean composition of Bristol Bay over time,” Grace said.

So, what kind of insights can isotopes deliver with regards to salmon diet? Salmon can be considered generalists in their diets, eating whatever is available. In an ocean with small fish, this is what salmon would eat. If there is more zooplankton, salmon would eat that instead. Each thing has a very distinct isotope signature. If the isotope is a lower value, it’s zooplankton, and if it’s a higher value, this corresponds with small fish.

“Because salmon eat whatever is available, it’s possible to make assumptions about what is most abundant in the ocean based off what the salmon is eating. If the isotopes show that in the 1960s salmon ate mostly zooplankton, but today they eat mostly small fish, then it can be hypothesized that for whatever reason, the ocean composition has more small fish and fewer zooplankton than it once did,” Grace shared. “If these patterns can be connected to changes in climate, it may be possible to more accurately predict what the ocean composition will look like in another 60 years,” she added.

Grace is just at the beginning of this research project as part of her masters program thesis. Spending time in Alaska this summer in the same place where scales have been collected since the 1960s, she’s enjoying combining field elements of research with lab work involving stable isotope analysis, mechanical work and modeling.