A University of Washington citizen science program — which trains coastal residents to search local beaches and document dead birds — has contributed to a new study, led by federal scientists, documenting the devastating effect of warming waters on common murres in Alaska.

From tropics to temperate: The shifting breeding ranges of seabirds amid climate change

Foxes are migrating northward, frogs are climbing higher into the mountains, and walruses are hauling out closer to shore. Across the globe, species are shifting their ranges in response to environmental changes driven by climate change. However, seabirds face distinct challenges in adapting to these shifts. Unlike many species, seabirds rely on both suitable terrestrial and marine habitats for survival. While they can follow their prey as it moves northward in the ocean, successful reproduction depends on finding quality terrestrial breeding grounds that overlap with these changing marine environments.

The California Channel Islands may serve as a critical climate refuge for seabirds. Situated at the convergence of the cool, nutrient-rich California Current and the warmer, more tropical Southern California Countercurrent, the archipelago offers a uniquely diverse oceanographic environment. This position supports a diverse mix of northern and southern breeding seabirds found nowhere else in the world. Channel Islands National Park, which spans four of the islands, provides an added layer of protection for these vulnerable species. At least 16 seabird species currently breed on the islands, and the park is estimated to provide habitat for 99% of the breeding seabirds in Southern California.

- Brown Booby chick on Sutil Island. (Credit: David Pereksta)

- Adult Brown Booby with chick on Sutil Island. (Credit: Jim Howard)

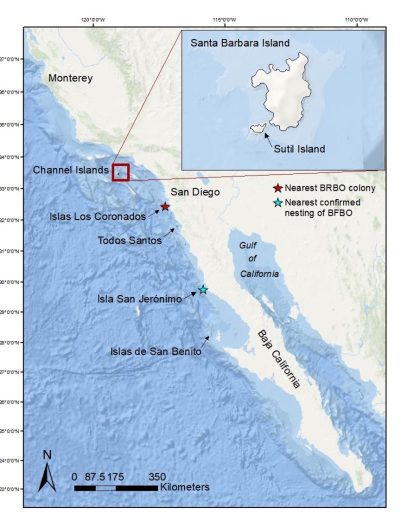

Amelia DuVall, a PhD candidate at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences (SAFS) and a member of the Washington Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, is a scientist in the world of seabirds. In September 2024, she and her colleagues published a paper in Western North American Naturalist reporting on the breeding range expansion of two pantropical seabird species—the Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster) and the Blue-footed Booby (S. nebouxii). Previously, the northernmost breeding locations for both species were in Mexico. Brown Boobies are found in tropical oceans across the globe, and Blue-footed Boobies along the west coast of the Americas from Peru to Baja California, Mexico. However, both now breed at Sutil Island, a small rocky island off Santa Barbara Island in Channel Islands National Park, marking the first confirmed breeding records for Sula species in the continental United States.

Sutil Island is a steep small (13-acre) island that is closed to the public and rarely accessed by researchers. Due to limited access, researchers have tracked the gradual arrival of boobies by observing the island from a boat with binoculars, from nearby Santa Barbara Island, or through aerial photographs taken by helicopter. Brown Boobies were first observed on Sutil Island in October 2013, with breeding confirmed four years later, in October 2017. The number of nest sites attended by adults or containing chicks grew from four in 2017 to 31 in 2022, and the total number of birds at the colony increased to 164 by September 2021. Blue-footed Boobies were first sighted in August 2018, with breeding confirmed two years later when a hybrid Brown Booby/Blue-footed Booby chick was documented.

So, what’s driving the northward range expansion of these seabird species? A key factor is rising sea surface temperatures. Warmer waters affect the physiological and ecological tolerances of seabird prey, causing shifts in prey distribution toward cooler northern waters. In essence, as the fish move, the seabirds follow. The 2014-2016 marine heatwave was particularly significant, as it triggered a northward shift in the distribution of larval Pacific sardines and anchovies, with the highest concentrations of larval fish in the northern California Current observed in 2015 and 2016—levels not seen since the 1990s. The collapse of the sardine fishery between 2009-2013 in the northern Gulf of California—the likely source population for these seabirds—may also have contributed to the expansion of their breeding range. As climate change progresses, the northward shift of these crucial prey species is expected to continue over the next century, with sightings of Sula species becoming more frequent as far north as Washington State.

The other researchers involved in the study are Jim A. Howard, California Institute of Environmental Studies, David M. Pereksta, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region, David M. Mazurkiewicz, Channel Islands National Park, Adam J. Searcy, Creosote Biological, Phillip J. Capitolo, Institute of Marine Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, and Tamara M. Russell, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego.