What brought a group of high schoolers to SAFS to teach a lesson on Pacific salmon and chemicals? It all started with an interest in ecology in 9th grade biology class, and a quest to find a relevant, local topic that they could base a research project on. Since then, Iris Zhang, Ivy Wei, and Sylvia Mei from Redmond High School—now sophomores in 10th grade—found a graduate student researching this topic, and developed a lesson centered on the effects of 6PPD-quinone on salmon.

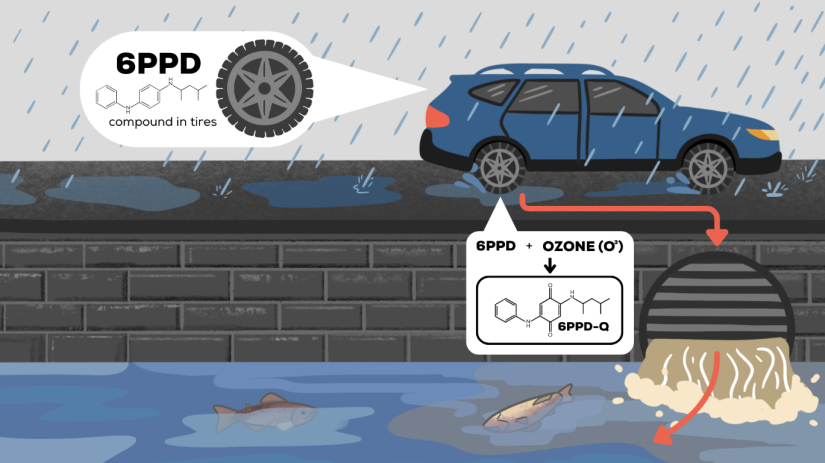

“After asking our biology teachers for ideas, one suggested looking into the impact of tire residue on salmon populations,” Ivy, Sylvia, and Iris shared. “The more we learned, the more fascinated we became—especially when we realized how local and urgent the issue was.” Present in vehicle tires is the chemical 6PPD, which prevents them from breaking down due to reactions with ozone in the air. When this chemical reacts with ozone, it forms 6PPD-quinone (6PPD-q), which then runs off into stormwater when it rains. 6PPD-q has been found to be toxic to aquatic organisms, such as coho salmon.

Here’s where Amirah Casey enters into the story. After reaching out to Dr. Nat Scholz, program manager of the NOAA Ecotoxicology team, he put the high schoolers into contact with Amirah, a SAFS graduate student studying the effects of urbanization and climate change on natural systems. “Amirah offered us the opportunity to co-develop a curriculum centered on the effects of 6PPD-quinone on salmon,” Sylvia, Iris, and Ivy said. The lesson is part of a wider outreach effort to middle-schoolers, undertaken by SEAS (Students Explore Aquatic Sciences), a group based in SAFS.

“These students have created an awesome simulation and lesson, and in April, they came to UW to present this to the SEAS board members and other graduate students, who were all very impressed with their work,” Amirah said.

Opting to make this lesson as enjoyable as possible, the high school group decided to structure it as a mystery. “The most entertaining part about creating the lesson was definitely how we decided to frame our lesson as a mystery,” they said. “Figuring out how to present the information in a way that wouldn’t reveal the final answer was an obstacle for us, but it encouraged us to problem solve and we came up with fun solutions throughout this process.” A unique benefit for them was also casting their minds back to being middle schoolers and thinking of the ways in which the lesson could be of most interest to that age group. “When going through and editing the lesson, we tried to take the perspective of being a middle schooler and this encouraged us to do our best at including enjoyable activities and questions,” they shared.

One of the main components of the curriculum was an interactive simulation that focused on mirroring the effects of 6PPD-q on coho salmon in different stream types. “Students going through the lesson work in small groups, each with their own container setup representing an environmental condition. Inside each container were laminated salmon cutouts to simulate live fish in the ecosystem,” Iris, Ivy, and Sylvia said. “We purposefully set this lesson up as an investigation where students are introduced to the problem and must figure out the culprit to the mysterious salmon deaths.”

Not only did they get to design a lesson, but the group also got the chance to present it in a visit to SAFS, building skills that will come in handy throughout the rest of their future educational and career journeys. “We were thrilled when we were given the opportunity to present to the SEAS members. It was very exciting to see our work with Amirah turn into an interesting and engaging lesson,” they said. “Although we’ve had experience presenting short lessons to our peers before, this was our first time presenting a full-length lesson with interactive activities and worksheets. The SEAS board members were very lovely to present to, extremely welcoming, and helped us feel confident. Plus, they helped us imitate a real middle-school classroom by pretending to be students!”

Subject experts and educators: that’s how Ivy, Sylvia, and Iris describe themselves now as a result of this project. “While creating this lesson plan, we became specialized in an issue impacting our local environment: the toxic effects of 6PPD-q on salmon populations in Puget Sound area. Not only did we get to try out the role of being an educator—which gave us a deeper appreciation for our teachers—but we also became scientists who were conducting research to understand more about the impacts of this chemical,” they said.

Continuing on the scientist route is the goal for this group of high schoolers. “While it’s still early, we know we want to pursue some branch of biology, and this project has taught us important research skills and helped us become more aware of current environmental issues,” they said. What’s next for them after high school? “We hope to build off the skills gained from this project to do our own research in university, such as conducting hands-on lab experiments—be that on an environmental issue or another field of biology,” Sylvia, Iris, and Ivy said. “Ultimately, we feel incredibly lucky to have had the opportunity to work on something so meaningful with an amazing mentor, and we know that the skills and experiences we’ve gained on this journey will stay with us.”