Last year, we spoke with SAFS undergrad, Michael Han, about receiving the NOAA Hollings Scholarship and where this would take him over the next year. This summer, Michael has split his time between NOAA’s HQ in Silver Spring, Maryland and NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center (AOC) in Lakeland, Florida. His internship has been focused on NOAA’s Hurricane Hunters, aircraft which fly into the world’s worst weather to collect data which assists forecasters in making accurate predictions during hurricanes, and helps hurricane researchers achieve a better understanding of storm processes. Read about Michael’s summer internship below.

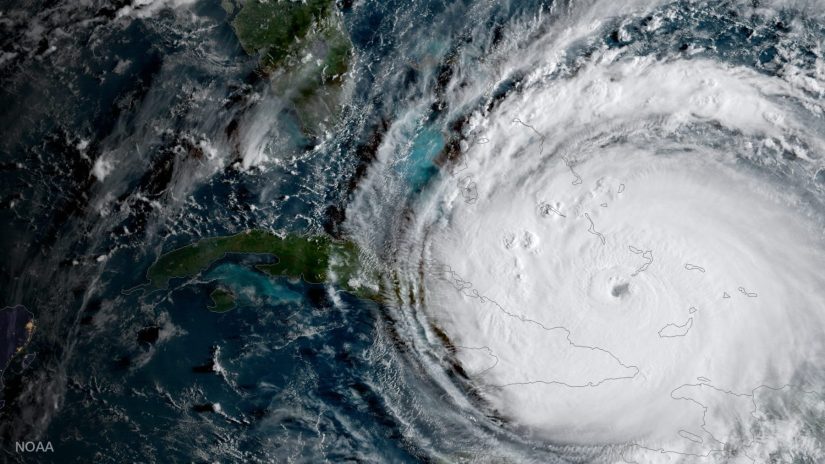

The main project I was working on with NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations (OMAO) was a visualization of Hurricane Hunter aircraft flying through Hurricane Milton. Milton was the strongest Atlantic storm last year in 2024, exceeding Cat 5 speeds and being one of the most intense storms ever found over the Gulf. NOAA OMAO was heavily involved in forecasting and researching it, conducting 10+ research flights from October 6-10, 2024. I retrieved flight track coordinates and plotted them with the help of ArcGIS and Python, then overlaid a sheet of satellite images of liquid and solid precipitation to show the hurricane itself. This was a visualization that was created specifically for the Science on a Sphere, which is a large globe model present in Smithsonians and many other museums across the country.

My time was split between headquarters at Silver Spring, MD and NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center (AOC) in Lakeland, Florida. Although NOAA’s aircraft can be all over the world at any given time, all 10 are ultimately stationed at AOC. This includes four DHC-6 Twin Otters, three Beechcraft King Airs, two WP-3Ds, and one Gulfstream 4. Being there allowed me to take video footage with a 360 camera of all the different aircraft and splice segments into the visualization for a more complete view of the mission. AOC was definitely the highlight of my internship since I was able to get out of the office and have some hands-on learning with the planes. However, my favorite part was getting to talk to all the NOAA Corps officers and ask them about their career paths, the planes they fly, and how they contribute to the scientific process.

Besides my main Hollings project, I also shadowed my mentors around, attended a whole bunch of meetings, and worked on some fun side tasks such as mapping out NOAA’s flights on the Texas floods or gathering info on the P-3’s scientific instrumentation.

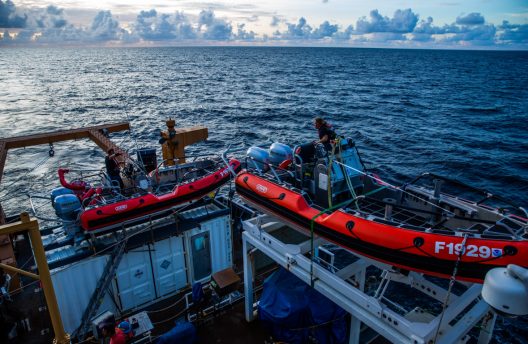

- View from above…

- …taken in a NOAA Twin Otter.

The pictures above show the NOAA Twin Otter in transit from Hagerstown, MD to Lakeland, FL. NOAA operates four DHC-6 Twin Otters which are part of the light aircraft fleet. They stay busy 365 days a year conducting scientific research on missions such as air chemistry, LIDAR, coastal mapping, and marine mammal surveys. When this picture was taken, the aircraft (N46RF) was on its way back to AOC after completing a month long study on ozone concentrations near Baltimore, which involved sampling the atmosphere for certain compounds that contribute to the formation of ozone. The research was done in predetermined grids east of the city as the prevailing winds during the study were westerly.

My main role while flying in the Otter as a student pilot was to get some on-the-job training from the NOAA Corps officers flying the plane up front. I learned about the locations and functions of the various instruments present in the cockpit and how NOAA flights communicate with Air Traffic Control (ATC) when operating research missions.

- Gulfstream 4.

- WP-3D Orion.

The two photos above are taken in the heavy plane hangar at AOC! The NOAA fleet currently includes three heavy aircraft and seven light planes. The heavy aircraft visible in these pictures are the Gulfstream 4 (left) and the WP-3D Orion (right). These planes are the backbone of NOAA’s hurricane hunting fleet and provide the data researchers need to accurately forecast storms. The P-3 is a large, turboprop aircraft tasked to fly straight into hurricanes at an altitude of 8-10,000 feet. The cone shaped object mounted on the back end of the plane is a tail-doppler radar (TDR) which is used to vertically scan the storm. This is combined with a horizontally scanning radar mounted on the belly to create a 3D cross section of the hurricane, which is sent to the National Hurricane Center, real time, to be immediately incorporated into forecast models.

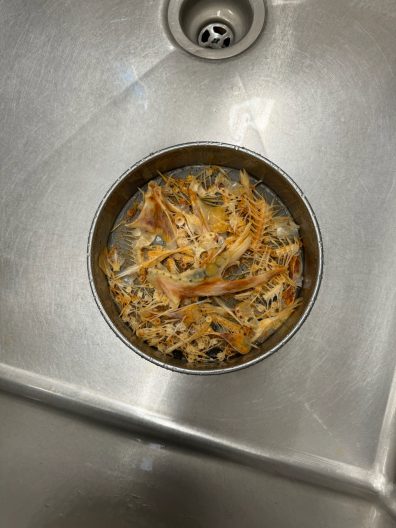

The G4, nicknamed Gonzo, is a heavily modified business jet also outfitted with a tail doppler radar (TDR) and various scientific instrumentation. Both planes also have the capability to launch dropsondes and unmanned systems such as drones from launch tubes. Dropsondes are small cylinders released from the underside of the aircraft and record metrics such as temperature and humidity as they fall, and the data is processed by a special dropsonde operator in the back. Unmanned systems provide some similar capabilities but are able to remain in the air for longer periods and return more readings.

Decals or victory marks can be seen in the photo above, showing all the hurricanes this P-3 has flown through, along with the countries it has operated in! The marks face left (counterclockwise) for Northern Hemisphere missions and vice versa. Hurricane Milton, which I worked on, is visible in the bottom left corner.

The preflight process involves a mission brief where the objectives are laid out and roles of everyone on board are made clear. The flight plan is discussed and the pilots go over their physical and emotional wellbeing. Once that’s completed they’re out to the aircraft, and pictured above is the pilots conducting an exterior walkaround of the plane. This entails checking the tire and brake systems, looking for cracks in the structure, and ensuring the flight controls have full freedom of movement.