It’s not all work while visiting the Alaska Salmon Program camps for the summer field season. Students head up to southwest Alaska, some for over three months, and downtime is a chance to explore, connect with their peers, and experience living in a field camp.

Some students are avid fishers and get to experience fishing in a location that vacationers usually pay a large sum to enjoy. Ryan Luvera, a SAFS and Marine Biology double major entering his third year, shared: “Outside of a typical workday I love to fish, and the fishing up here is truly world class.”

Whether you have visited the camps in person or only seen pictures, the location continues to be one that awes. Hiking Church Mountain, a familiar sight towering over the Lake Nerka field camp, is a tradition among those who spend time with the Alaska Salmon Program. “It was very steep but so worth it, both for the views and the sense of accomplishment. We got a bonus lesson on the history of glaciation in the valleys visible from the top. It was amazing to see the concepts physically laid out in the landscape,” Emma Meyer, a junior at SAFS, said.

Some of the more subtle experiences are among the most memorable. “One of my favorite things to do was have lunch in the tundra,” said Callie Murakami, a SAFS major now in her third year. “Some days we packed lunches and snacks to have while we were out, and we would sit in the open tundra to eat. The ground was soft, there were crowberries and cloudberries growing everywhere, and we could all chat and take a break. Even in the rain, nothing could beat a tundra lunch.”

Building a sense of community is a key part of the experience, from studying and working during the day, to pitching in for mealtimes and spending evenings together. “As a class, we all enjoyed each other’s company and would often play speed solitaire, cambio, and bananagrams in the evening after dinner,” shared Emma Bell, who will soon be graduating from SAFS. “One night we made popcorn and had a movie night which was also really fun.”

For many students, visiting Alaska is a highlight of their time studying at the University of Washington. “Last year I was at Friday Harbor Labs, and I thought that was going to be the peak experience of my college experience, and then I came to Aleknagik,” said Ryan Luvera. “This is truly an experience like no other, being able to be in living quarters with so many brilliant minds, I wish I could spend every summer here!”

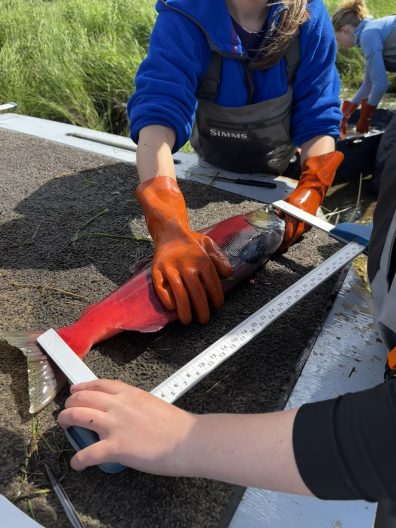

For others, it’s an opportunity to see another side of the fishery that they have experience with. Naomi Prahl, a SAFS major going into her senior year, shared: “I work as a commercial fisherman in the Bristol Bay sockeye salmon fishery, which is the fishery that utilizes the ASP data for their management decisions. Working in the fishery gave me a first look at how incredible the Bristol Bay ecosystem is, and getting to be a student with ASP this summer felt like a full circle moment. I got to see the ‘behind the scenes’ of the fishing job that I love so much. There was something almost magical about getting to see the salmon in every life stage through the class this summer after working a fishing season beforehand.”

Putting into practice key skills learned throughout their academic journeys is a central part of the Alaska Salmon Program and sets students on course for a range of opportunities in the future, from further study in graduate programs to careers in academic institutions and fishery-related fields. “I learned a lot of valuable skills about field and professional work, such as preparation and flexibility when it comes to working in the field, and how to work and communicate better as a team,” shared Callie Murakami.

How do students find out about this opportunity to spend a summer in Alaska? “While I was attending community college my only intention after I graduated was to transfer to SAFS,” said Emma Bell. “I was constantly looking at the SAFS webpage and seeing all the cool opportunities they offered and thought that the Alaska Salmon Program seemed really incredible. When I saw the flier posted, I was so excited to fill out an application.”

Hundreds of students from UW have spent time with the Alaska Salmon Program over the last few decades, immersing themselves in one of the world’s most remarkable ecosystems. For future students, Naomi Prahl shared some advice: “Just get excited. It’s such an incredible and unique opportunity and I think the way to appreciate it fully would be to dive in headfirst. Don’t hide your enthusiasm and share what you’re excited to learn about. When you get there, try everything. Don’t shy away from asking questions and trying things you have no experience with. Take full advantage of the learning opportunities presented.”