The SAFS Boots in the Mud fund is a special opportunity to provide our students with materials and equipment needed for immersive learning opportunities.

On the ice and from the air: Combining Indigenous Knowledge and multidisciplinary science to investigate Alaska’s ringed seals

In the Arctic, where temperatures are rising at nearly four times the global average, a collaborative effort, combining Indigenous Knowledge with multidisciplinary science has been used to investigate the denning habitat selection of Alaska’s ringed seals.

During the Ikaaġvik Sikukun (Iñupiaq for “Ice Bridges”) project, researchers from the University of Washington School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences (SAFS), Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Native Village of Kotzebue, NOAA, and Farthest North Films collaborated with an Elder Advisory Council of Iñupiaq Qikiqtaġruŋmiut Elders with extensive personal history of subsistence hunting and experience on sea ice. The scientists and Elders worked together to identify the research topic and then continued to collaborate throughout the project on the study design and interpretation and dissemination of results.

Essential to Arctic ecosystems, sea ice and snow play a critical role for both marine mammals and Indigenous Peoples in these regions. During an unusually warm spring in 2019, Jessica Lindsay, a SAFS PhD candidate advised by Professor Kristin Laidre, worked with the Ikaaġvik Sikukun team in Kotzebue Sound, Alaska, to investigate how warming temperatures impact where ringed seals (“natchiq” in Iñupiaq) make their dens.

Ringed seals are a valued nutritional, spiritual, and cultural resource for coastal Indigenous communities in the Arctic. A key component of this study, published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series in February 2023, was knowledge co-production, which is a research approach that integrates scientific and Indigenous ways of knowing to produce novel insights.

Ringed seals in Alaska are found in the seasonal sea-ice zones of the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas. They are uniquely adapted to occupy areas of landfast ice by maintaining breathing holes in the ice. As the snow accumulates, these breathing holes are converted to snow-covered dens for resting and birthing in the spring. Climate change is impacting ringed seal habitat in a number of ways, including decreasing spring snow cover for dens.

In the winter of 2018–2019, much less sea ice formed in Kotzebue Sound compared to previous years, giving seals less space for resting and denning.

Bobby Schaeffer, a Kotzebue Elder and co-author of the study, said, “For the first time in Iñupiat history, 90% of Kotzebue Sound was ice-free the entire winter. That has never happened before.”

Breakup of the sea ice also happened earlier in the spring while pups may still have been nursing. That April and May, Lindsay worked with Schaeffer and other researchers out on the sea ice to measure ringed seal habitat features, such as snow depth and surface roughness, which helps snow drifts to form. The research team used drones, or “unoccupied aerial vehicles,” outfitted with cameras to collect images of the sea ice near Kotzebue, which Lindsay then combed through to find seals. Satellite imagery, combined with ground-truthing from on-ice surveys, was used to help describe the snow and ice characteristics at the places where seals were found.

Using the data from both aerial and on-ice surveys, habitat selection models showed that ringed seal groups and pups selected for deeper snow depth and intermediate surface roughness. The habitat conditions in winter 2018–2019 were not typical of previous years in Kotzebue Sound but may be considered indicative of what ringed seal habitat conditions could be like in a future of dwindling ice.

“In a way, the unusual winter in 2019 was a good research opportunity,” Lindsay said. “It gave us the chance to see how ringed seals use the habitat that’s available to them when they don’t have access to a ‘normal’ amount of snow and ice.”

This study came up with a new way to quantify ringed seal habitat by using satellite image characteristics. Brighter areas of the satellite image tended to have deeper snow depth during on-ice surveys, and similarly, areas of the satellite image with high variability in brightness tended to match up with areas on the ice that were rough instead of flat. As sea ice becomes less safe to travel on, remote methods like satellite imagery will become increasingly important for studying seal habitat.

Ringed seals are listed as “threatened” under the US Endangered Species Act, and this study will help wildlife managers better understand what habitat features are important for them as climate change continues to affect Arctic Alaska.

“These types of focal studies are critical to the conservation and management of ice-dependent species. We need to collect data that help us understand the impacts of climate change and we need to work with Indigenous communities while we do it,” says Laidre.

The Ikaaġvik Sikukun project is an important example of how knowledge co-production can ensure that research is successful and that the results are valuable to Indigenous communities who are reliant on marine resources. Insight and involvement from Elders was essential throughout the project.

Cyrus Harris, a Kotzebue Elder and co-author of the study, said, “I see the greatest benefit of Ikaaġvik Sikukun as coming together and really documenting the Indigenous perspective of living on the ice and sea, and looking at how things were back then to today with climate change. It’s been in the minds of Iñupiaq People from time immemorial—this project is just putting the science into it.”

Arctic Indigenous communities such as Kotzebue are on the front lines of climate change, with substantial environmental changes observed even within Elders’ lifetimes, and knowledge co-production studies may become increasingly important for communities and for scientific research in a warming Arctic.

Interested in more information about this project?

- The full study was published on February 9, 2023, as a feature article in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series (MEPS). It is available to download at https://www.int-res.com/articles/feature/m705p001.pdf.

- Watch the documentary film about the project, produced by Farthest North Films: https://youtu.be/P9RzfGtLWHo.

- Project partners:

- Elder Advisory Council: John Goodwin, Cyrus Harris, Bobby Schaeffer, Roswell Schaeffer Sr.

- Principal Investigators: Christopher Zappa (Lead PI), Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University; Donna Hauser, International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks; Andy Mahoney, Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks; Alex Whiting, Native Village of Kotzebue; Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films; Ajit Subramaniam, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University

- Additional team members: Peter Boveng, Marine Mammal Laboratory, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, NOAA-NMFS; Nathan Laxague, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University; Carson Witte, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University

- Read other papers from the Ikaaġvik Sikukun project:

- Co-production of knowledge reveals loss of Indigenous hunting opportunities in the face of accelerating Arctic climate change

- Thin ice, deep snow and surface flooding in Kotzebue Sound: landfast ice mass balance during two anomalously warm winters and implications for marine mammals and subsistence hunting

- The winter heat budget of sea ice in Kotzebue Sound: Residual ocean heat and the seasonal roles of river outflow

- Read Ikaaġvik Sikukun newsletters here

- All seal research activities were conducted under NMFS MMPA Research Permit No. 19309

FINS for the win!

Ever wondered how money raised from the sale of FINS merchandise gets used? Look no further—here are some recent stories from SAFS students who have directly benefited from funds raised by the Fisheries Interdisciplinary Network of Students (FINS), housed at the UW School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences.

One of the best ways for graduate students to present their research to an extensive, global audience and interact with national and international colleagues is to attend conferences relevant to their field of study.

Thanks to the work of FINS and contributions from our community through the purchase of merchandise graduate students like Maria Kuruvilla, Sarah Yerrace, Zoe Rand, and Sarah Teman have been able to attend academic conferences and take part in research expeditions.

In her 5th year as PhD candidate in QERM and SAFS, Maria used her FINS award to travel to an Animal Behavior Society Conference in Costa Rica in 2022. Because of the COVID pandemic, this was Maria’s first opportunity to travel to an international conference, and she valued the ability to network with international colleagues and discuss her work with other experts in the field. As an added bonus, this was an opportunity for her to make new friends and visit a new country.

Sarah Teman, a master’s student at SAFS, received a FINS award in Winter 2023, which helped to fund her travel to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, to participate in a special USGS-led polar bear research expedition. This feeds directly into her study focus on the health of polar bears in the southern Beaufort Sea. Understanding the health of these apex predators is not only important from a wildlife or ecosystem health perspective, but also for Indigenous communities around the Arctic who rely on bears as an important food and cultural resource.

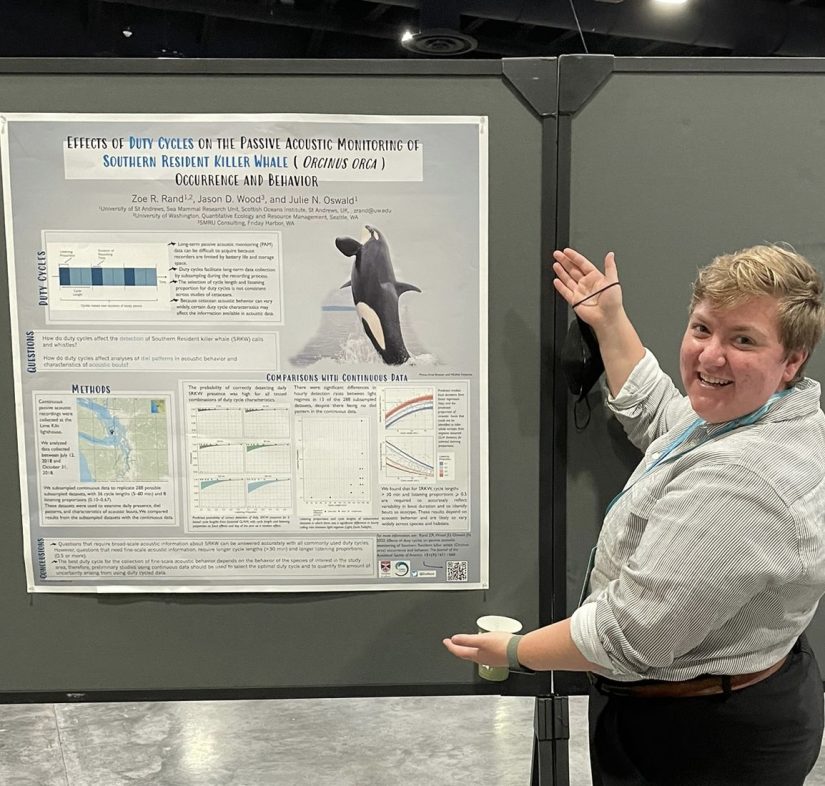

A FINS award in 2022 allowed Zoe to travel to the Society for Marine and Mammalogy conference. Because she had begun her graduate studies during the pandemic, this was an extra special moment—her first chance to present in person at an academic conference as a graduate student. While presenting her poster, Zoe had the opportunity to connect with scientists from around the world who share similar research interests, and she’s excited to continue strengthening these relationships as she progresses in her PhD studies and in her future as a scientist.

Professional development is a critical part of being a graduate student. Thanks to FINS, Sarah Yerrace was able to travel to Orlando, Florida, for the Association of Dive Program Administrators Annual Symposium and the Dive Equipment and Marketing Association Show in 2022. It was an incredible in-person networking opportunity, with so many dive professionals that she had only ever corresponded with via email—finally, she was able to put faces to names!

Community is important for our graduate students here at SAFS, and we’re thankful for the opportunities opened up to them in both their research and future careers by the awards funded through FINS and supported directly by you.

Stay tuned for more updates on how this year’s awards will be used by our students, and if you haven’t yet done so, be sure to check out the range of merchandise available for purchase to support them.

Interested in how you can support FINS?

Check out the range of merch online! Mugs, accessories, shirts, stickers and sweatshirts!

Stop by their special booth in person during the UW Aquatic Sciences Open House on Sunday May 21st.

Explore the evolutionary ecology of marine mammals in new class

In a new class taught by Dr. Amy Van Cise, students can dive into the world of evolutionary ecology of marine mammals.

FISH 497B MWF 12:30–1:20 pm

- Explore the diverse and integral ecological roles played by marine mammals in our global aquatic ecosystems, from coastal and riverine to open ocean and deep ocean environments.

- Examine the major evolutionary adaptations driving the radiation of mammals into the aquatic environment and into a diverse array of ecological niches.

- Consider the evolutionary strategies and ecological roles that are used by marine mammals and how those roles help shape aquatic ecosystems.

- Learn about ecological concepts such as food web dynamics, predator-prey interactions, and trophic cascades; animal movements and distributions; community assemblages; and ecological drivers of isolation, divergence, and mixing.

- Consider our own species’ role in the evolutionary ecology of marine mammals.

Instructor Pre-reqs

- Marine Biology/Ecology (FISH 250, BIOL 220, FISH 270, FISH 311, or equiv);

- Scientific Writing (FISH 290, MARBIO 205, FHL 333, or equiv)

What lies beneath the waves at Seattle’s waterfront?

As part of the UW Wetland Ecosystem Team’s Seattle Seawall Fish Monitoring Program, an underwater video from 2022 has been released.

Documenting what lies beneath in Year 5 of the project in 2022, the video is compiled from snorkel and SCUBA surveys to monitor effectiveness of the Seattle seawall rebuild for improving habitat for juvenile salmon and other nearshore fishes.

For more information visit http://depts.washington.edu/wetlab/

SAFS Professor joins Radio Tacoma’s Climate Talks

Skating on thin ice: polar bears in a warming future

On International Polar Bear Day, the plight of these apex predators could not be more evident, as a result of a myriad of threats to their existence due to climate change.

As their name suggests, polar bears live in the Arctic polar regions of Canada, Greenland, Russia and Alaska. Kristin Laidre, a UW scientist at SAFS, shares that polar bears require ice for almost every aspect of their existence, including feeding, moving, breeding and in some places, maternity denning.

Why is International Polar Bear Day celebrated on February 27th? Because it’s the time mothers and cubs are denning across the Arctic and highlights just one of the existential threats posed by a warming climate at a particularly vulnerable time in a polar bear’s life.

Studying ecology and population dynamics of Arctic marine mammals, Laidre uses data on individual movements, foraging behavior, and life history to unite behavioral, population, and evolutionary ecology. In this time of global climate change, her research on the impacts of a warming world on ice-dependent species is of particular interest.

The conditions of a polar bear’s body are heavily impacted by the loss of ice according to Laidre. With not enough time to feed and gain the fat resources needed to survive the year, the loss of sea ice causes a cascade of issues including on reproduction, survival, and population abundance.

But is there hope for the future? Can polar bears adapt to a warming climate? Across the polar regions, Laidre says that the type of sea ice, the rate we are losing sea ice, and the productivity of the ecosystem is resulting in a variability of response of the world’s 19 polar bear populations.

However, this regional difference is underpinned by a clear prediction: a 30% reduction in the global abundance of polar bears is forecast over the next several decades if greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced.

So what inspires a new generation of scientists to get involved in polar bear research? Sarah Teman, a MS student at SAFS working in Kristin Laidre’s lab, became interested in studying polar bears due to their unique physiology and life history, and the fact that they face very challenging threats.

In her thesis project, conducted under the ‘One Health’ concept that the health of wildlife, ecosystems, and humans are deeply connected, she aims to measure the health of polar bears in the southern Beaufort Sea over time.

Understanding the health of these apex predators is not only important from a wildlife or ecosystem health perspective, but also for Indigenous communities around the Arctic who rely on bears as an important food and cultural resource.

Meanwhile, PhD student Jenny Stern, also working with Laidre, was drawn to the field due to the extreme nature of the Arctic ecosystem and is exploring what is required for top predators to survive in a rapidly changing climate.

Focusing on the Baffin Bay polar bear subpopulation, Jenny’s dissertation looks at feeding ecology and asks some important questions such as how diet varies among demographic groups and space-use strategies.

Jenny analyzes hair and fat samples collected from captured polar bears using stable isotopes and fatty acid analyses and combines this data with movement data from adult females tracked with satellite collars.

When asked about a memorable field experience, she shared that during a 40-day Arctic Research Expedition on a US Coast Guard icebreaker, she got to see a polar bear approach and stand on its hind legs whilst the ship was stuck for a few days in an ice floe. Watching her subject of research exploring and moving through its environment was a favorite memory of hers.

Research remains a critical frontier in efforts to combat the negative impacts of global climate change on species and environments around the world, and the research underway at SAFS highlights just some of the scientific work involved in that effort.

Trawlers working amidst a whale ‘supergroup’ raise red flag about human-whale conflicts in a changing ocean

In a study led by Stanford University and Lindblad Expeditions, and co-authored by Trevor Branch from SAFS, scientists observed close to 1,000 fin whales foraging near Antarctica, while fishing vessels trawled for krill in their midst.

HistoryLinks interviews Jason Toft about the Seattle Waterfront

Read about his involvement in designing the replacement seawall along Seattle’s central waterfront and the key design features devised to make the environment as hospitable as possible for juvenile salmon, especially Chinook and Chum salmon, as they out-migrate from the river system to the ocean.

The giants of the sea

The biggest animals to have ever lived on our planet, blue whales are a charismatic species found across the world’s oceans.

Ranging in size from 79 ft in the Indian Ocean’s pygmy blue whale subspecies to more than 100 ft in Antarctic blue whales, these marine mammals were once hunted to near extinction.

In order to reconstruct past level of whales and discover if blue whale populations were recovering or not after the banning of commercial whaling in the 1980s, scientists have developed models that explain both old whaling catch records and modern-day counts.

Whaling records were incredibly detailed, recording data on every whale caught: species, size, sex, weight, fetus information, who caught them, the nationality of the boat, and date.

These historical datasets were used in decision-making by the International Whaling Commission to realize the Antarctic blue whale was almost extinct and to put a full moratorium on commercial whaling of the species in the 1960s.

Today, researchers like Professor Trevor Branch at UW are using statistical methods and models to study different whale populations across the globe and judge recovery levels.

He has been doing this work for decades. Fitting a model to data sets, he reconstructed what levels of whales there were, are now, and will be in the future, and judging whether they are in recovery or not.

There are many success stories. Almost every large whale population is recovering because whaling was the single biggest impact on these marine mammals in the past. Humpbacks are doing very well, and the blue whales on the Pacific Coast of the US have numbers suggesting they are fully recovered. Others like Antarctic blue whales are recovering but at very low levels, perhaps only 1% of pre-whaling levels.

Not all large whale populations are in good shape, however. North Atlantic right whales are still dying from entanglement with fishing gear and ship strikes, causing a decline in their numbers and raising the risk of extinction given their small population size.

Branch says it’s important to highlight the success stories in conservation of large whale species. Putting research intro practice, sharing why and how it helped recovery, and using it for other populations is vital.

His current work is focused on the assessment of pygmy blue whale populations in the Indian Ocean, with every population having a unique song. The whales repeat these songs over and over, and they are thought to have a mating function since only males sing them. These distinct calls stay stable over many decades, and he is using this information to figure out where each population resides, and therefore how many were caught from each during the whaling era. This will help him to assess trends in number over time for each of these populations… all based on their song!

On World Whale Day, we’re recognizing the importance of whales to the planet’s ecosystems and celebrating the recovery levels seen in most species whilst continuing to conduct research to tackle the continued negative impacts on the few that are still in danger due to human actions.