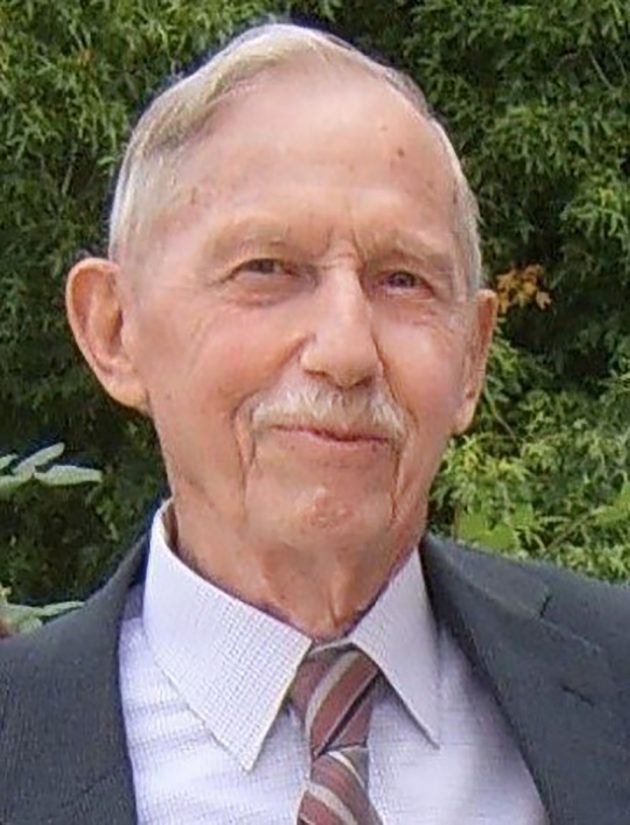

September 6, 1926–March 17, 2021

We thank the Liston family and SAFS faculty and students for their contributions to this memoriam. Some content was adapted from The Seattle Times obituary published on May 16, 2021.

John Liston, an esteemed microbiologist and retired member of the UW Fisheries faculty, passed away on March 17, 2021. John was renowned for his work on foodborne microbes and marine microbiology. He mentored numerous graduate students and played a key role in the professional development of several women scientists, including Dr. Rita Colwell (PhD 1961) and SAFS Professor Emerita Frieda Taub (PhD 1959, Zoology, Rutgers).

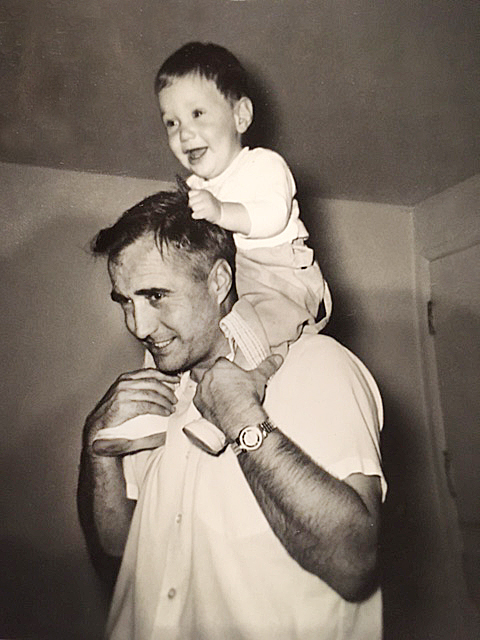

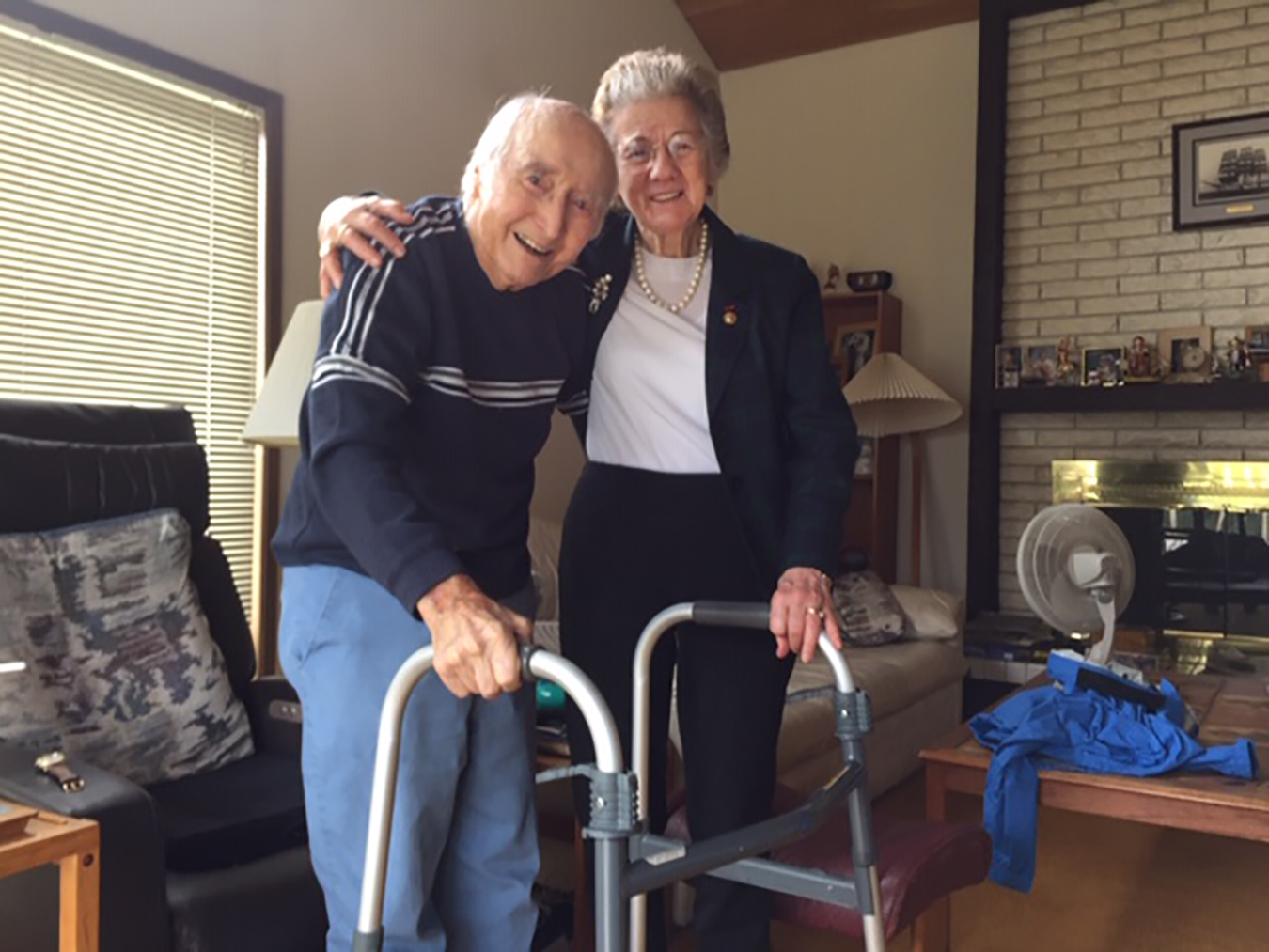

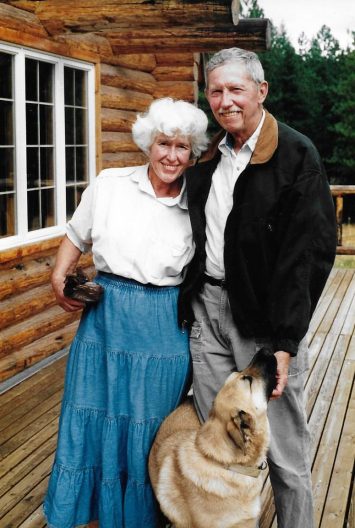

John was born and raised in Edinburgh, Scotland. He attended the University of Edinburgh, where he met his wife, Doris. He earned his PhD in Microbiology at the University of Aberdeen Scotland in 1955 and was offered a faculty position at UW Fisheries in 1957. He accepted the offer and moved his family to Bothell, Washington.

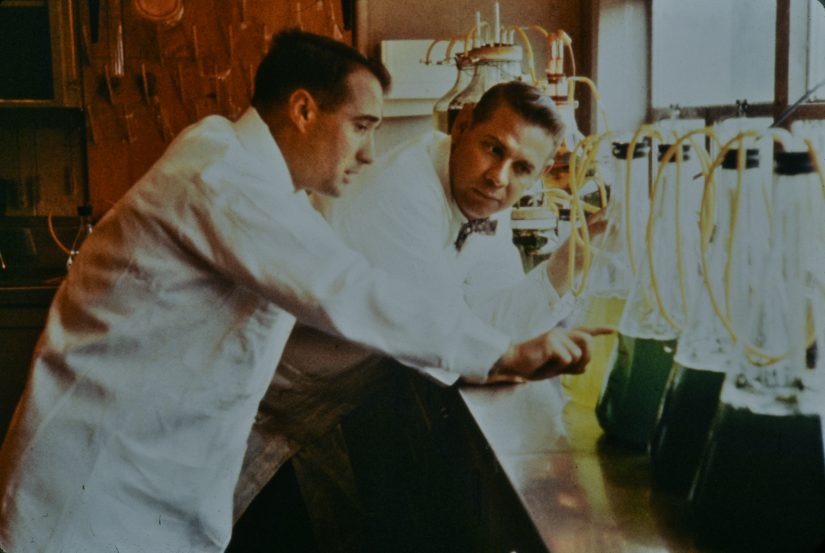

When John joined the Fisheries faculty, a food science division already existed. Under his direction, that division developed into the Institute of Food Science and Technology (IFST) in 1969, and John led the unit until retiring in 1989. Initially, research at IFST was focused on seafood microbiology issues, including better canning methods to prevent botulism and improved shelf life for fresh fish.

IFST’s research scope expanded greatly under John’s leadership. A new direction focused on detecting mutagen formation in processed foods, while another investigated different feed ingredients and formulations, and feeding strategies for coldwater fish aquaculture.

During John’s tenure as director, the IFST faculty included four women. SAFS Emeritus Professor Frieda Taub noted, “Besides supervising female doctoral students, John was instrumental in recruiting Barbara Rasco, Faye Dong, Barbee Tucker, and me to Fisheries faculty positions. This was unusual at UW.”

During Frieda’s time at Fisheries, John became her mentor. She said he “fought hard for my promotions, eventually to full professor with tenure in 1971.” Notably, many of his female graduate students and staff went on to successful careers in science, including serving on college faculty at a time when that was rare.

John also supported basic science in oceanography. He supervised graduate student John Baross (PhD 1973; currently UW Oceanography faculty) in his study of deep-sea microbes. John said, “His breadth of knowledge was impressive, and he supported my research ideas despite them not being funded through his projects. I always looked forward to lunch walks along Lake Union, where we would discuss science, literature, philosophy, or whatever came up at the moment.”

Perhaps less well known were John’s efforts to address “brain drain” of foreign students who did not return to their home countries, where they were needed to help improve food security and safety. Frieda said, “He developed programs that brought students here for short time periods, and faculty went overseas to teach short courses.”

John’s research led him to pursue microbiology studies in places such as Iran, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Latin America, and many European nations. He was a prolific writer, having published or co-authored more than 150 scientific papers on fisheries microbiology and technology.

Rita Colwell is one of John’s more renowned former graduate students. After earning her PhD (1961), focused on microbiology under his direction, she served on UW Fisheries’ research faculty before eventually becoming the first woman director of the National Science Foundation (1998–2004). Rita reflected: “John was not your typical professor. He trusted me to set up his microbiology lab.” When John arrived at UW, he actively explored new technologies and new ideas: “As a result,” said Rita, “we were the first to apply computer analysis to marine bacteria.” She added, “He encouraged his students to read classic literature and poetry. He also had a beautiful singing voice and often performed at parties.

Another student of John’s—Marleen Wekell (PhD 1975)—said, “John treated all students equally well regardless of gender or ethnicity. He was an effective mentor for all of us.” Marleen added, “He always insisted his students defend their positions with data and logic and often took an opposing view to see how we would fare under scathing criticism. This experience served us well.”

Faye Dong, who retired in 2012 from her position as head of the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, University of Illinois, Urbana–Champaign, was on the IFST faculty during John’s directorship. She noted: “He was a wonderful mentor and model for young faculty. He was highly respected in the fields of food microbiology, marine microbiology, and food technology.”

Faye further confirmed John’s exceptional support of women in science: “He provided professional support and opportunities for women faculty members—including Barbara Rasco and me—equivalent to what he provided for male faculty members.” Faye added that John never asked anyone to do anything that he was not willing to do himself—be it to teach a class, mentor a student, or serve on a committee.

Barbara Rasco (currently dean of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Wyoming) said, “John focused on ensuring that scientists were well rounded—experts in their field, but with a solid grasp of how the research fit into a multidisciplinary context before this was in vogue.” Barbara commented on his sense of humor: “He was serious without taking anything too seriously.”

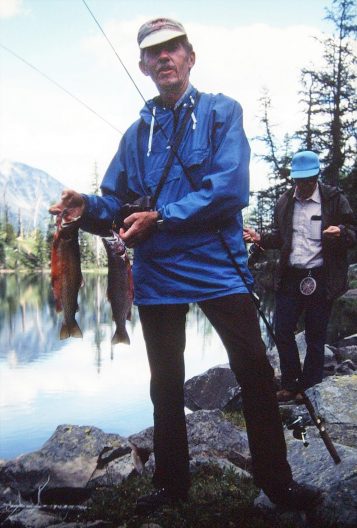

John was a family man and enjoyed hiking, camping, fishing, and skiing with his three children and four grandchildren. His daughter, Fiona, spoke about his dry sense of humor: “He threatened to grade his graduate students’ papers by tossing them down the stairs and giving the highest grades to those that fell the farthest!”

Despite his wicked humor, Fiona said, “Dad had a very positive outlook on life and was kind in all things. He gave to every charity that solicited from him.” She spoke to John’s championship of women’s rights: “I was surprised to read that this was even a “thing” because he never thought to treat different genders or cultures differently. People were just people to him, and we grew up with this, so it just felt natural.”

John is survived by his daughters, Rosalind Liston-Riggs and Fiona Liston, and son, John D. Liston, and four grandchildren.

The Liston family requests that charitable donations in remembrance of John be made to Habitat for Humanity.

Dear Friends

Dear Friends

PhD candidate

PhD candidate