My interest in fish and marine mammals started young. While other kids were memorizing baseball card statistics or the pathways on Super Mario and Zelda, I was memorizing fish identification books. My interest was driven by the fact that my father was a fisheries and marine mammal biologist, and I was fascinated with fishing and fish in general.

During my childhood, I had many opportunities for my love of fish and marine mammals to grow. My father coordinated the marine mammal stranding network for the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Northwest Regional Office and was the lead on marine mammal issues, and I got to accompany him to strandings on the Washington coast. My dad also worked with a team to address the issue of Hershel, the California sea lion at the Ballard Locks. In addition to time with my father, I also spent a lot of time fishing at the Edmonds Pier with my brothers, and I maintained up to three aquariums while breeding cichlids and observing their behaviors.

Given these opportunities, it is not surprising that upon completing high school, I chose to apply to the University of Washington to join the School of Fisheries—only I wasn’t accepted. I was a goof off in high school and rarely turned in my homework, which resulted in a subpar GPA and a not very surprising rejection by UW. I had only applied to UW, knowing that I wanted to work with fish or marine mammals, and the rejection was an embarrassing revelation alerting me that I needed to put in the effort if I wanted to do the things I enjoy in life.

I was very fortunate that I had filled out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) for Western Washington University, Washington State University (WSU), and UW even though I only applied to UW. A week or two after UW rejected me, I received a letter from WSU saying that they had received my FAFSA application but could not find my application for enrollment. They offered me a chance to send in another application, and when I did, WSU accepted me. I often wonder where my life would have gone if they had not sent me that letter.

At WSU, I found success in the classroom while taking classes in the Natural Resource Science program. I was very grateful to WSU for giving me an opportunity to prove myself in college, but I still wanted to pursue studies of fish and marine mammals and knew that my best opportunity would be at the UW. After my sophomore year at WSU, I applied to UW again, and this time, I was accepted as a transfer student.

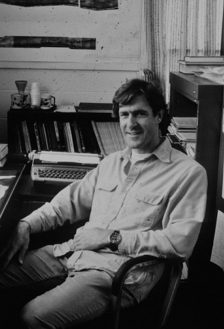

At UW, I wasted no time in enrolling in classes in the School of Fisheries. I had finished nearly all of my prerequisite and general education classes at WSU, which allowed me to focus on upper division fisheries science and statistics classes while at UW. I completed enough course work by the end of the first quarter of my senior year to graduate, but instead I decided to add a second degree in Wildlife Science and stay through the end of my senior year. I graduated in 2002 with BS degrees in Fisheries Science from the School of Fisheries and Wildlife Science from the College of Forest Resources.

The course I enjoyed the most was a six-week course that immersed me and five other students in the beautiful field settings at Lake Aleknagik, Lake Nerka, and Lake Iliamna in the Bristol Bay region of southwest Alaska, with faculty Daniel Schindler, Thomas Quinn, and Ray Hilborn. At the time I took the course, I visualized a future career of studying bears as an interface of fisheries and wildlife. I learned quickly in Alaska that the study of bears was not in my future—I was too allergic to grass.

During college, I also pursued work and volunteer opportunities that helped shape may career. In 1999, I had the opportunity to observe the Makah whale hunt and to help perform the necropsy on the whale they successfully harvested. It was an eye-opening experience on treaty rights and how important traditional activities can be for an indigenous group. I also worked for Edmonds Parks and Recreation. I thought at the time that being a park ranger could be a fun career—instead, the experience of cleaning toilets and picking up the litter of inconsiderate guests soured me on the idea. I also worked for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Marine Mammal Program. This was my first experience in marine mammal science, and despite spending most of my time cleaning fish bones in seal scats, I really enjoyed the job and cemented my desire to work with marine mammals in the future.

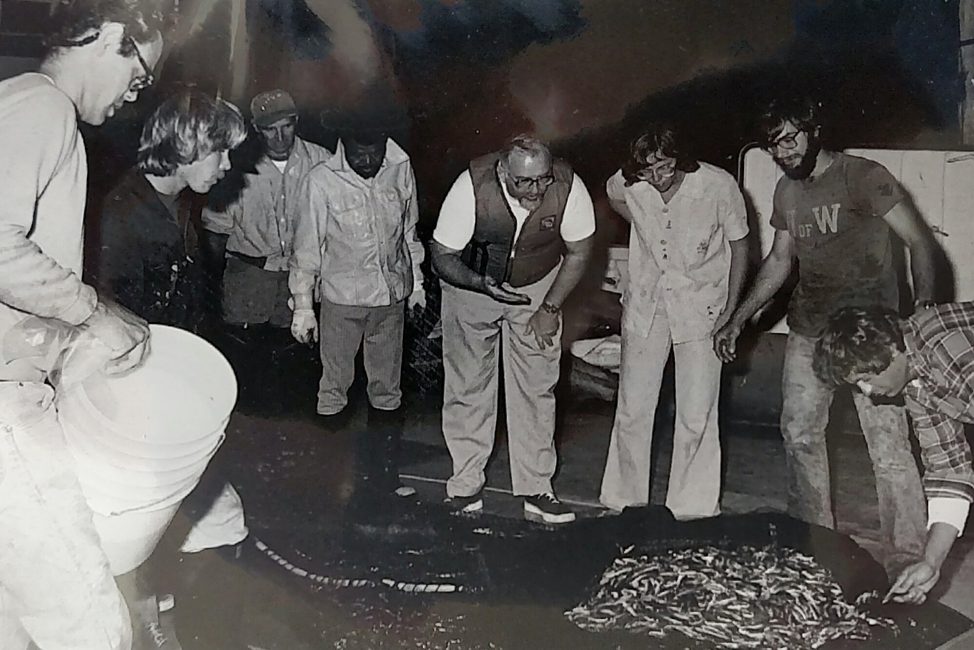

Following college, I worked a couple of jobs that expanded my world views as a biologist before returning to school for an MS degree at Oregon State University. My first job was a six-month contract as an at-sea observer in the West Coast Groundfish Observer Program. I suggest that all graduates in fisheries science or management should work at least one contract as an observer. As an observer, I received a hands-on point of view of how fisheries work, how markets affect catch and discards, and how fisheries management decisions directly affect fishermen and their families. My next job was as a contractor to NOAA’s National Marine Mammal Laboratory. This reignited my interest in marine mammal science and exposed me to a variety of marine mammal studies and research methodologies.

Since 2007, I have worked for the Makah Tribe as their marine mammal biologist. I did not expect to spend my career in this position, but I have now worked here for 11.5 years and do not see another position that would work as well for me. I love several aspects of this job. First, I help the Tribe protect their treaty rights through improving understanding of marine mammals to allow sustainable management. I feel proud that my work is helping to address a social injustice issue as well as contributing to research and management. Second, I am able to study many topics; my primary study species are gray whales and Steller sea lions, but I also work on other marine mammals, including California sea lions, killer whales, and humpback whales, and non-marine mammals, including river otters, Pacific halibut, and purple olive snails. Third, I have had an opportunity to travel and see the world while participating in the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission. Last, I have developed great relationships with co-workers, collaborating scientists, and the Makah community.

The foundation of knowledge I gained while a student at UW has helped me throughout my career. In my professional life, I have worked with UW professors on a variety of projects and have collaborated with former classmates on research projects. I hope that the School of Fisheries will continue its role of shaping the careers of fisheries scientists and managers for another 100 years.